Most of us don’t know exactly why we like this song.

I know, I know… that can’t possibly be true, but I’ve talked to a lot of people about it and the verdict (mostly) is that it’s just a generally favorable piece of art that we all seem to enjoy… even though we sort of don’t really know what’s going on the whole time.

It’s sort of like cooking with onions, or a classic Shakespearean plot, or casting Loretta Devine as someone’s mom in a movie, we’re unsure of exactly why we like it, but we know we do.

Let me explain.

When I was a child, I liked this song for how catchy it was. At 8, I could sit in the backseat or on the bus home from school and just wait for the chorus (or the part where they say “run Forrest, run” at the end) and jam TF out. A simpler time, and song, it was.

And then as I got older, I found myself really appreciating the beat and what Mannie Fresh did on this entire album, 400 Degreez. I was sure this was the reason I loved it most. But nope, there was more to appreciate.

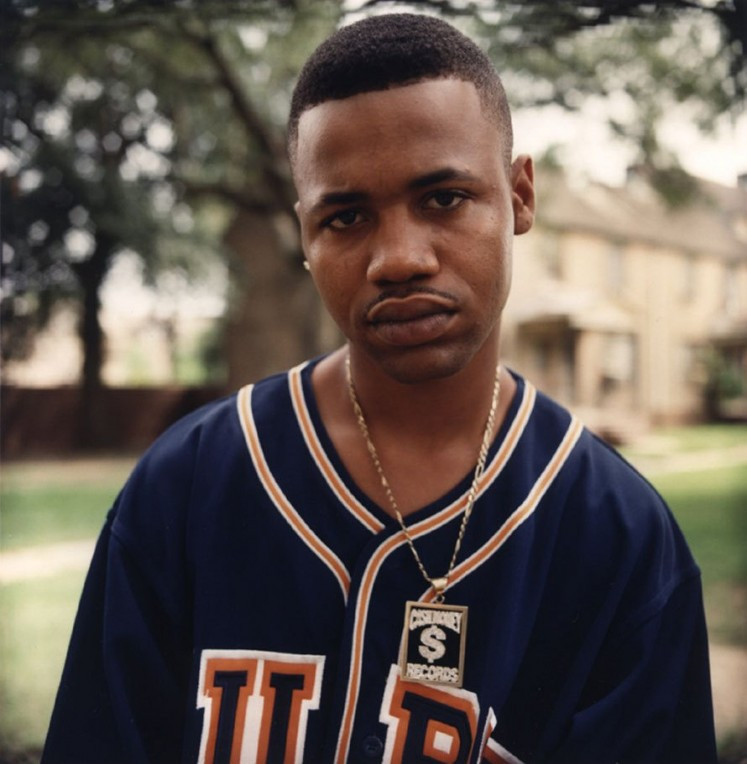

Maybe a few years after that, I grew to love just how classic the music video is. Juvie standing in a muddy puddle in some of the whitest Reeboks I’ve ever seen is an image that’s hard not to appreciate. I figured I’d reached peak appreciation for the song, but then…

Eventually, as it always does for me, it came back to the song’s lyricism and its dedication to theme. This is the honey I’ve been stuck to ever since, and it was then that I finally knew why I like this song.

This is a coming of age story, no different from some of our favorite movies (or plays). A street tale, told in 2nd person hood satire, shining a brilliant light on the humanity of poverty itself.

And that satire, plus some foreshadowing, irony, and tragedy, started me thinking that maybe this could actually be massaged into a Shakespearean play.

You think I’m playin’, ha?

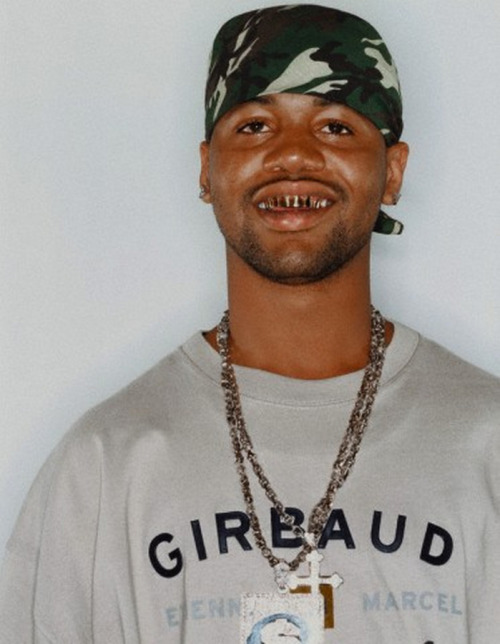

Originally, catchy phrases he uses like “twankle yo’ golds” and “dat fire green” sound more like parsley sprinkled all over a few verses just for the f*** of it, but when you judge them through the fabric of the entire song, they land far more impactfully than that.

In fact, by the time it ends, we realize he’s done just the opposite of that, everything here is purposeful. He uses those catchy phrases to draw in our subject, enticingly laying out the most triumphant elements of the hood (drugs, women, money, cars, etc.), and then wisely distancing himself from them in the same breath.

And the beauty of it all? He doesn’t just outwardly state any of his points (Shakespeare would never do that). Instead, he cloaks that satire and irony in other thematic vehicles to make us work for it, starting with our subject’s Mercedez-Benz which he references multiple times.

“That’s you wit that bad a** Benz, ha?” (1st verse)

“You spent 70 on your Benz, ha?” (2nd verse)

“You ridin’ in the Benz on 20-inch rims, ha?” (3rd verse)

What begins as genuine admiration of the Benz in the 1st verse, quickly turns to static as Juvenile grows more and more dismissive of our main character and his actions. We know by the chorus that the guy is just trying to “remain a G until the moment he expires”, but it’s about more than just the car… and that’s what actually grabs Juvie’s attention the most.

Not unlike Dom Kennedy’s “Black Bentleys”, this Benz is the model of success, and ultimately the definition of failure for our friend and this lifestyle, and Juvenile knows it from jump street.

Nino Brown couldn’t make it out alive. Tony Montana fell short too, and so will this guy, if he goes down this road. And you can bet your bottom dollar he’s seen New Jack City and Scarface, but that would never stop him from trying.

This, too, is the humanity of poverty itself and some brilliant foreshadowing.

And that’s pretty much how the song rolls on. Juvenile exploring different elements of the hood and handing out backhanded compliments as rhetorical “ha” questions (a total of 64 times) as he watches this dude’s inevitable rise and fall.

You see, while our subject is trying to get his “block on fire”, Juvenile sees an easy target; someone who may need to slow his roll and watch his back. But that doesn’t mean he’s going to be the one to do it. And to be honest, the moment he saw that $70k Benz with those rims, he knew nobody else would either. Juvenile is just the narrator.

Somewhere between sounding a warning siren and shooting a warning shot, every time our subject hears “ha”, he can’t help but feel both the contempt and care in Juvenile’s words. They’re smug, yet sincere, as if to say “You’re a grown man, so I’m not gonna tell you what to do, but you ain’t the only grown man around here, if you know what I mean.”

Again, we see the humanity of poverty itself. Juvenile knows this dude is in over his head, and there are several times when he’s trying to tell him he’s gone a tad too far. But our poor subject can only see these warnings as goals and accomplishments. Certainly, he’s headed for doom:

“That’s you that can’t keep an old lady cuz you keep f****** her friends, ha?”

“You wanna bust one of the n*****’ heads, ha? You ain’t scared, ha?”

“You come up with them n*****, ha? You stuck with them n*****, ha?”

“You wanna be the only n**** with rocks, ha?”

“When you paid you got beau-coup places to go, ha?”

Sex, violence, loyalty, power, money… they all have limits, especially in the Magnolia Projects. Enticing, as they’re presented, our subject has gone a few too many steps in the “right” direction, and Juvie is trying to make it plain. Each of his statements breathe life into the sentiment that too much of anything is bad for you. Our subject is flying too close to the sun and he’s about to get his a** bust… and everyone knows it but him.

Between those twankled golds, that fire green, and that badass Benz, we’re only left to assume our friend didn’t make it very long. That’s probably why the song ends the way it does, with him running for his life.

And then there’s little 8-year-old me, riding in the backseat or on the bus home from school screaming “Run Forrest, run Forrest, run!”. I surely couldn’t have known just how fitting an ending to this tragedy it really was, I just knew that it was the best part of the song. And outside of the lyrics actually being “run for it, run for it, run”, I guess 8-year-old me knew some things.

That little refrain toward the end is truly this song’s final touch of humanity: a wise word to the wicked to get the hell out of dodge. It’s a rather quiet, albeit thrilling, finale to this Shakespearean-style coming of age story that’s probably as old as time.

Because whether they got him that day, or the next, or maybe even never at all — there will always be another badass, $70,000 Benz on 20″ rims driving through muddy puddles in the hood.

Because after all, all the world’s a stage, and the men and women are merely players. That was that nerve, ha?

[Extra]Ordinary is a series of underrated, underestimated and under-appreciated people in Hip Hop. They are the ones who get looked over for one reason or another despite having rangy influence, tremendous vision, and/or a s***-ton of talent. These are some of your favorite rappers’ favorite rappers; and you ain’t eeeem know it. My job here is to enlighten their artistry in your eyes so that they may have the chance to evolve from being extra ordinary to extraordinary. Originally published on Grits & Gospel.