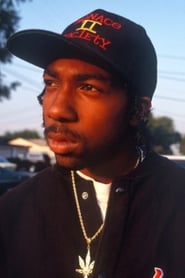

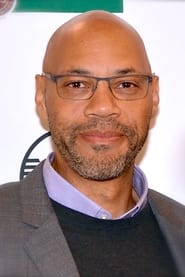

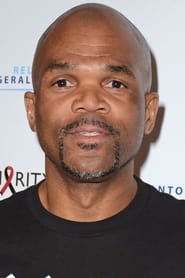

As the MC for the hip-hop act the Roots, Black Thought has been unconventional even by the standards of that iconoclastic group. Where most rappers seek out publicity, Black Thought has avoided it and has rarely even been interviewed over the group’s 20-year existence. “Some people—they like to talk, they like to interview…,” Black Thought pointed out to Paul Farber of Philadelphia Weekly. “I come from a household where it’s like, ‘Close that door.’ As soon as the sun goes down and the street lights come on, you close the curtains so people can’t be lookin’ up into your s-t. I’m that way in life.” Despite his reticence, however, Black Thought’s creative contributions were central to the success of the Roots and became even more important as the group set hip-hop longevity records in the 2000s and approached their third decade of existence.

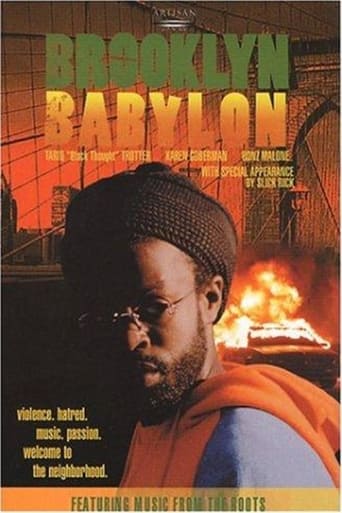

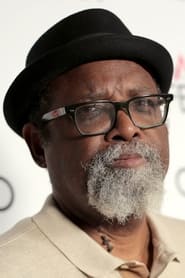

Black Thought was born Tariq Luqmaan Trotter on October 3, 1972. He grew up in the Point Breeze neighborhood in south Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Although he concealed them from public view for many years, the facts of his childhood were grim. His father, a member of the Nation of Islam‘s Fruit of Islam policing arm, was killed while he was a baby, and his mother was also killed when he was in the 11th grade. Black Thought’s brother Keith amassed a long criminal record.

Black Thought himself, however, seems to have channeled his reactions into creativity. He started rapping at age nine and won admission to Philadelphia’s prestigious High School for the Creative and Performing Arts (CAPA). At first he studied visual arts and thought about becoming an architect. He had an instinct for commercial success from the start—he made African medallions and sold them for ten dollars each to his fellow students. Black Thought had disciplinary run-ins at CAPA, starting on his first day with an incident in which he was said to have been caught in a bathroom with a senior girl dance student, and he was eventually expelled. He graduated from Germantown High School and went on to study at Millersville University and to take journalism courses at Temple University in Philadelphia.

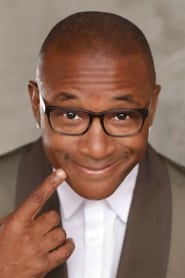

By that time he was already a star with a local reputation. “What set Tariq apart was that he had an amazing talent to play the dozens [competitive impro- vised insult rhyming],” fellow Roots member Ahmir-Kalib “Questlove” Thompson told Farber. In 1987 the pair formed a duo called the Square Roots and took their drum-and-rap act to clubs and talent shows. Not needing electronics, they were also free to take their act to the corner of Fifth Street at Passyunk Avenue in downtown Philadelphia, and in the summer of 1992 they earned some $4,000 in tips.

The Square Roots became the Roots, took on additional members (bassist Hub [Leonard Nelson Hubbard], rapper Malik B. [Malik-Abdul Basit], and “beat boxer” human percussionist Rahzel), and gained a regional reputation for its live, non-electronic take on hip-hop music. Around 1993 things started to happen quickly for the Roots. They were invited to play at a German festival, recorded an album, Organix, and parlayed the original appearance into a European tour. Word filtered back to the United States, and the Roots were signed to the DGC/Geffen label and released the album Do You Want More?!!!??! in 1995.

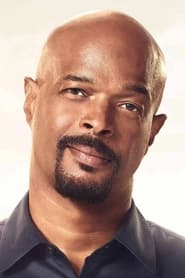

The group gained attention for its use of live instruments and limited recourse to such staples of hip-hop language as digital sampling (sometimes they sampled and looped their own rhythmic patterns, but the collage-like aspect of many hip-hop recordings was absent from their music). The Roots won fans among both urban and modern rock audiences. Although the loquacious Questlove was often seen as the group’s public face, it was Black Thought (after the departure of Malik B.) who provided most of the text content. His boasting raps reflected his early background in street and club “battle” performance, but there was also an element of social critique in his music. Some of his raps attacked the materialistic and misogynistic qualities of other hip-hop acts.

After the Roots continued to gain popularity with the albums Illadelph Halflife (1996), The Roots Come Alive (1999), and Things Fall Apart (1999), Black Thought planned to release a solo album of his own, tentatively entitled Masterpiece Theater. The album was eventually shelved because of disagreements between the Roots and their label (at the time) MCA; a solo Black Thought album would not have counted toward the group’s contractual obligation toward the label. Much of the material Black Thought had written, however, showed up on the next Roots album, Phrenology (2002). Black Thought also contributed raps and background vocals to recordings by other artists including the Pharcyde (Plain Rap), Common (Like Water for Chocolate, which also featured several other members of the Roots), and Jill Scott (Who Is Jill Scott?).

Indeed, Black Thought’s continuing development as a wordsmith was partly responsible for the ongoing success of the Roots, long after most of their hip-hop contemporaries had disappeared from the scene. The Roots returned with The Tipping Point (2004) and Game Theory (2006), ranging ever more widely in their subject matter. Black Thought’s more serious attitude, Questlove told Peter Rubin of XXL magazine, was the key to Game Theory: “Mostly, this is Tariq’s ongoing evolution,” he said. “Once you’ve mastered battling about your MC prowess, what do you do? I think Tariq has come to grips with his life. I slowly see him starting to open himself more and more and more.”

Partly Questlove was referring to the unreleased but widely circulated track “Pity the Child,” on which Black Thought, for the first time, addressed the tragedies of his childhood. “Certain joints are a lot more personal, self-reflective, than I may have pulled out before,” he pointed out to Rubin. A family also brought Black Thought to a new level of commitment; his son, and the boy’s mother, were trapped in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, and for several days Black Thought did not know where they were. Asked by the website tha Formula in 2007 about what motivated him, he answered, “I got a family to take care of and kids to feed. That’s my motivation, this is my job.”

Official site: The Roots