August 11, 2009. I walked into the FYE in the Gallery at Market East in Philly and headed straight for the new releases section. I had already gone digital with my iPod Classic but a new album dropped that day and I wanted an actual physical CD.

Entering the store, I felt a rush of excitement like I did back in the ’90s when a new release would necessitate a trip to the mall. It was tempered a bit because the album had leaked a few days earlier and I was already halfway through memorizing it, but ripping off that plastic and studying the liner notes, photos, and booklet is a feeling that can’t be replaced through the computer.

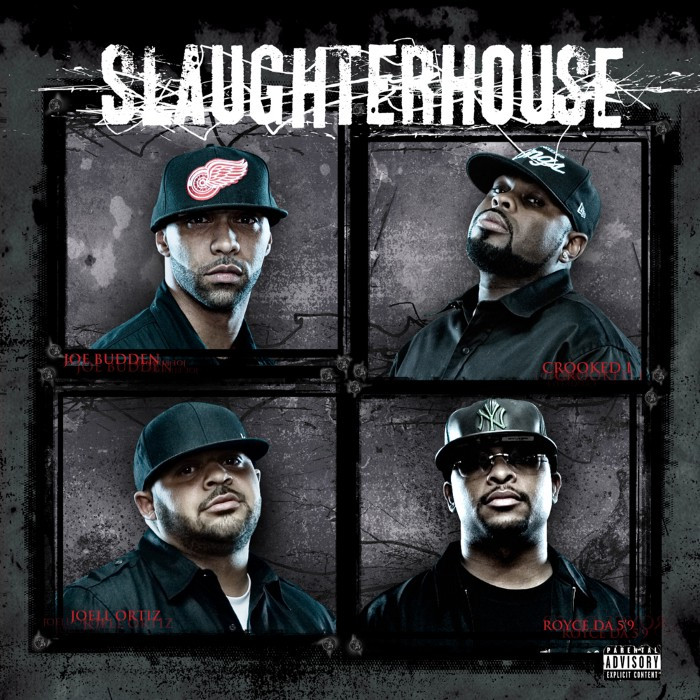

Slaughterhouse had unleashed their self-titled debut and I was determined to be one of the first to buy it. I was heavy into writing and commenting for XXL.comat the time and, for me, this supergroup represented a return to the rap of my youth, focused on battering rhymes over punishing beats. They were going to bring real rap back.

Complaining the state of lyricism was not new — Common released “I Used to Love H.E.R.” in 1994 and Rakim promised that he was bringing back “lyrics” and “skills” on his solo debut way back in 1997— but hip-hop was undergoing a seismic shift in the summer of 2009. Drake’s game-changing mixtape, So Far Gone, had dropped six months earlier; Kanye’s world-changing album, 808s and Heartbreak, four months before that.

I was getting older and I missed the old days.

I had been a fan of all four for years — Royce Da 5’9″ since the first Bad Meets Evil maxi-single; Joe Budden from his days massacring instrumentals on DJ Clue? tapes when everyone thought his last name was plural; Joell Ortiz since his days on Aftermath; and Crooked I from his time with Death Row and tracks with Tha Dogg Pound.

Four emcees, most of whom I had been checking for as far back as 1999, coming together to deliver what I and those of my ilk felt the game needed. We wanted them to force everyone to step up their pen game.

“We a outfit, equivalent to Voltron’s / That boy Crooked I’s equivalent to four arms / Joell Ortiz is the body / The cannibal-slash-killer, kill you then eat your body / Joe Budden is the pair of legs / He runs s*** alongside I, the apparent head”

The album dropped and while it wasn’t perfect — some of the beats could’ve hit a bit harder and the Fatman Scoop feature was regrettable — it included some absolute gems. It portended of bigger things to come while still giving those of us that were salivating for it all of the wordplay we could handle.

Unfortunately, there weren’t many of us.

Slaughterhouse, released by E1, peaked at number 25 on the Billboard 200 (though it did reach number two on the rap chart) and sold 19,000 copies its first week — for comparison, that number is still only a quarter of the tenth-highest sales of a hip-hop album that year (UGK’s UGK 4 Life moved 76,000 units its first week).

The debut Slaughterhouse album confirmed something disheartening we all knew already: super lyrical albums don’t sell.

“All you gotta know is Crooked I, Royce, Bless, and Joell / With Joe spell: No L”

Like so many creations, it wasn’t planned.

Midway through Joe Budden’s 2008 digital album, Halfway House, there’s a song that boasts five ink slingers spitting fire. It was reminiscent of the classic posse cuts from years earlier, like “Banned From T.V.,” “Leflaur Leflah Eshkoshka,” and “24 Hours to Live.” Titled “Slaughterhouse,” it featured Royce Da 5’9″, Joell Ortiz, Crooked I, and Nino Bless along with Budden.

That single song turned into a “movement,” an “epidemic,” and four of the five (all but Bless) continued to connect, bonded by their similar backgrounds — highly-respected, underground-embraced emcees that had suffered from label politics, which each addressed on the remix to Ortiz’s “Move On.”

Before the quartet officially joined forces, they were already recording together, releasing tracks like “Wack MC’s,” “Fight Club,” and “Onslaught,” all of which continued to whet the appetite for the group’s debut.

“Every twelve months it’s huntin’ season / They call us Slaughterhouse for a reason!”

While the first album didn’t necessarily sell out of stores, scores of Hip Hop purists were enthusiastic about the group. They stayed together. Like the Wu-Tang model, they dropped in on each other’s solo projects while still touring, working on group albums, perfecting their chemistry and advancing the collective.

They dropped the slim Slaughterhouse EP in 2011 and their first official mixtape, On the House, the following year only a few weeks before the release of their sophomore disc. It felt like they were finally about to get the shine that so many of us — probably including themselves — felt they had deserved for so long.

“Four of the best in the world, I’ll put an M on it / And if that ain’t enough, I’m puttin’ Em on it”

When rumors began to swirl that the group would sign with Shady Records — a theory bolstered by their standing behind Eminem during his scene-stealing “Forever” verse — it felt like a perfect combination.

Skills were not a problem, but perhaps the budgets (beats, marketing, etc.) were, so linking up with one of the most successful hip-hop artists in history, one who appreciates the art of writing rhymes as much as anyone, seemed like the answer.

After all, the same approach had made 50 Cent into a superstar and allowed G-Unit, Obie Trice, and D12 to go platinum while still allowing them to largely keep their identities, so a revival — Shady 2.0 — along with Yelawolf was a no-brainer.

It began with a feature on the Just Blaze-produced bonus track of Eminem’s Recovery, “Session One,” followed by a loosie with both Em and Yelawolf, “2.0 Boys,” the 2011 BET “Shady 2.0 Cypher,” “Loud Noises” on the Bad Meets Evil reunion album, and others.

Crooked, Royce, Ortiz, and Budden would continue to do their thing, but now they had the ear and backing of someone that could take them to the next level. When the only thing eluding you is commercial success, who better to sign with than the highest-selling rapper in history?

Initially, it worked.

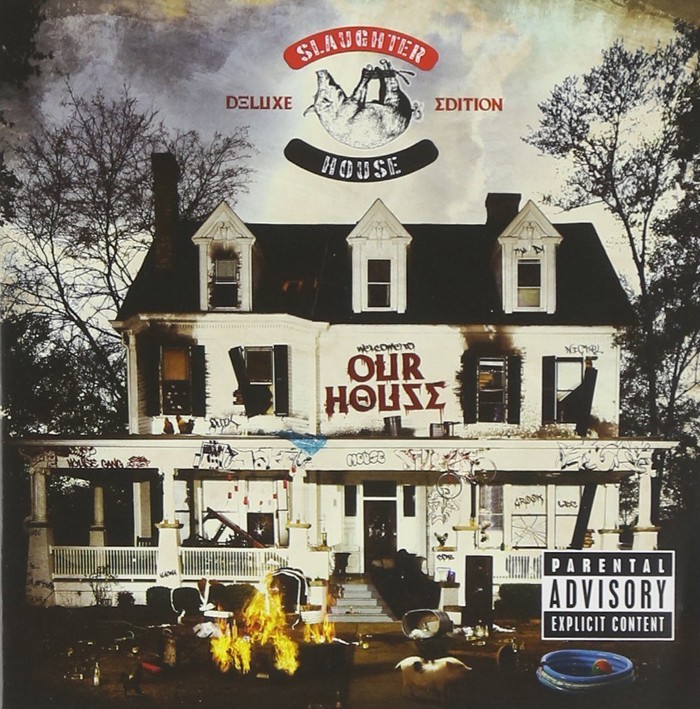

Welcome to: Our House dropped in August, 2012, only a few weeks removed from the three-year anniversary of their debut, and moved more than 50,000 units in its first week, good enough number two on the Billboard200 and the top spot on both the R&B/Hip-Hop Albums and Rap Albums charts. The response from critics was also largely positive.

A large cadre of the core fans was not as ebullient, however.

Glossy, polished production with pop sensibilities and crossover stars signing the hook works for later-career Eminem, but the beats, many of which sounded like they came from the studio sessions for Recovery, and the hooks, featuring the likes of Swizz Beatz and Skylar Grey, didn’t seem to fit with the foursome. There were a few highlights, like the street single “Hammer Dance,” the clever “Flip a Bird,” and the powerful “Die,” but they were lost in the morass of reaches for mainstream appeal.

Many of us that had been touting the greatness of Slaughterhouse and were excited for them to finally break through with Welcome to: Our House quickly realized that we preferred the Gangsta Grillz On the House mixtape, where they were doing what they do best rather than trying too hard to score a hit.

News of the fans’ disappointment even reached the album’s executive producer:

“That was another album that I felt like, Holy s***, people literally just trashed this. They trashed this album. There was a huge f*****’ backlash: ‘Aw man, this ain’t what we wanna here, it sounds too polished.’”

On his 2015 track, “Slaughtermouse,” Joe Budden provided a bit more insight:

“Maybe Slaughterhouse all thought that because Eminem was who Eminem was that our job would be easier, that his fans would be our fans.

We just had a lot misconstrued that we didn’t know. That his sound may work for us and we were learning on the fly. And later on it goes to say — we ‘learned what is good for the goose ain’t good for the gander.’

Eminem is great at being Eminem. He may not be great at being Slaughterhouse. Slaughterhouse is great at being Slaughterhouse.”

Therein lies the issue many had with the record. It sounded like Slaughterhouse was trying to be Eminem.

Compounding all of this, the album failed to maintain its initial momentum commercially and topped out at around 200,000, an enormous increase over the first album, but still short of expectations.

They had crafted an album that attempted to marry the two worlds of the streets and the charts but came up short, something that has happened to plenty of great artists. At the same time, there was a certain faction of hip-hop fans, who enjoyed the new wave of the genre and were tired of hearing about superlyricists, that were gleeful in the album’s disappointment.

Eminem laments those that were were “critiquing these guys who are f****** wordsmiths,” and while he’s correct, there is more to an album than only the lyrics and, for many, the entire vibe of Slaughterhouse’s Shady Records debut just didn’t feel right.

“F*** record sales or who the machine markets best”

Just like the first time around, it felt as if it would only be another speed bump.

Over the next few years, while discussing and prepping their next album for Shady, Glass House, which was supposedly being executive produced by Just Blaze, they continued to diversify with their own individual projects on which they all appeared, from mixtapes (“Monsters in My Head” on Crooked’s Psalm 82:v6) to albums (“Brothers Keeper” from Joell Ortiz’s House Slippers) to other groups (“Microphone Preem” on Royce and DJ Premier’s PRhyme).

n addition to dropping other tracks from time to time, they also popped up on the Shady XV compilation (“Y’all Ready Know) in 2014 and the Southpaw soundtrack a year later (“R.N.S.”), as well as a second mixtape, House Rules, that, like its predecessor, was well-received by the online masses and has been downloaded nearly a quarter-of-a-million times to date. It showed “promising signs of things to come.”

Or so we thought.

The wait for the third album — and the question of whether they could manage to find the perfect balance between the sounds of the first two — continued.

“You mighta heard the rumors / They thought it was three-quarters of the Slaughter left”

When the group collaborated on the track “Chopping Block” for Royce’s mixtape, The Bar Exam 4, it had been five years since Welcome to: Our Houseand things seemed different.

Glass House was still sitting on the shelf and while some group members continued to promise that the new album was on its way, others became frustrated with the lack of progress.

Budden, who had started a podcast two years earlier and was in the process of transitioning from artist to broadcaster, even announced that he was retiring from music as a solo artist, though he would continue to record as a member of Slaughterhouse.

Then, in April, 2018, Crooked I (now KXNG Crooked) took to Instagram to announce he was leaving Slaughterhouse, not due to any beef but seemingly their old nemesis, label politics, stating that the “group ain’t rapping no more.”

While there was speculation (hope?) that the remaining three would carry on, that was not the case.

Then, in August, Budden announced he was done recording, with or without the group.

All of this news came on the heels of Budden calling “Untouchable,” Eminem’s song from Revival that addresses police brutality, “trash” and “one of the worst records I’ve ever heard.” Following Em’s response in an interview and on his song “Fall” off Kamikaze, Budden responded that he’sbeen better than Eminem “for a decade.”

Criticizing the head of the label to which your group is signed, regardless of whether he’s an artist or not, is not usually a savvy business move, particularly when he signed you after a disappointing first album. It’s also not the best way to get your long-delayed album released. According to Crooked, Budden’s words ultimately torpedoed that hope:

“It definitely affected Slaughterhouse. Because me and Royce was working behind the scenes, trying to get the [Glass House] album out to the people. [The ‘Untouchable’ critique] was like a grenade; he took the pin out and tossed that b****.”

Budden agreed, saying the album is “never seeing the light of day.”

Slaughterhouse was no more.

Hopes for a reunion were once again raised when three of the four members connected for the remix of Joell Ortiz & Apollo Brown’s track, “Timberlan’d Up,” but the members have all agreed it’s not happening.

As far as Glass House, it has become the rap version of the Snyder Cut, with the creator(s) claiming it’s complete and hinting it may soon come with fans clamoring for it to be released, whether legally or illegally.

“I don’t be f*****’ around on the microphone”

When considering album sales along with the drama that has ensued, it could be tempting to paint the Slaughterhouse endeavor as a disappointment, if not outright failure, but that would be shortsighted and, frankly, incorrect.

The group, which specialized in lyrical dexterity and rhyme schemes at a time when those things were becoming marginalized by both fans and artists (Jay-Z’s “D.O.A. [Death of Autotune]” came out the same summer as the Slaughterhouse LP), was always fighting against the turning tide of hip-hop and had to know that while their fans were both rabid and loyal, it wasn’t guaranteed that they would be legion.

Although they weren’t able to crack the code and sell zillions of albums, Slaughterhouse was more than simply a group of rappers that bonded over their disillusionment with the industry and appreciation for complex rhymes.

It was a movement. Like D-Block on the mixtape circuit at the turn of the century, they had the ear of the streets and had fans wearing out the rewind button and arguing who got the best of whom on nearly every track.

As a whole, it was greater than the sum of its parts, giving more shine to each member and helping them to shrug off their previous reputations while building something bigger. It boosted the visibility of the members while simultaneously promoting the group.

Slaughterhouse showed Joe Budden was more than “Pump It Up”; that Joell Ortiz was more than the guy that had been signed to Dr. Dre; that Royce Da 5’9″ was more than Eminem’s friend from Detroit; and that Crooked I was more than the guy that had been on the cover of XXL with Suge Knight.

Each member of Slaughterhouse was — and is — a wordplay wizard, a lyrical murderer. They are some of the greatest rhyme spitters of this era, if not ever.

Those of us that bought that first album back in August, 2009 had sky-high expectations and thought they’d be together thirty years later, but rather than mourn what it didn’t become, we should celebrate the fact that four talented, competitive artists who had all been jerked around by the system and never really had a connection beforehand were able to come together and create their kind of unapologetic music collectively for almost ten years.

They may not have become superstars and they may not have been able to fully bring real rap back, but maybe they helped it to continue on for a little while longer and influenced at least some members of the next generation while giving us old heads some of that raw hip-hop we grew up on.

That’s more than any of us could ask for.

Republished from THE PASSION OF CHRISTOPHER PIERZNIK

Christopher Pierznik is the author of nine books, including The Hip Hop 10 and Hip Hop Scholar, all of which are available in paperback and Kindle. In addition to his own site, his work has appeared on XXL, Cuepoint, Business Insider, The Cauldron, and many more. Follow him on Facebook or Twitter.