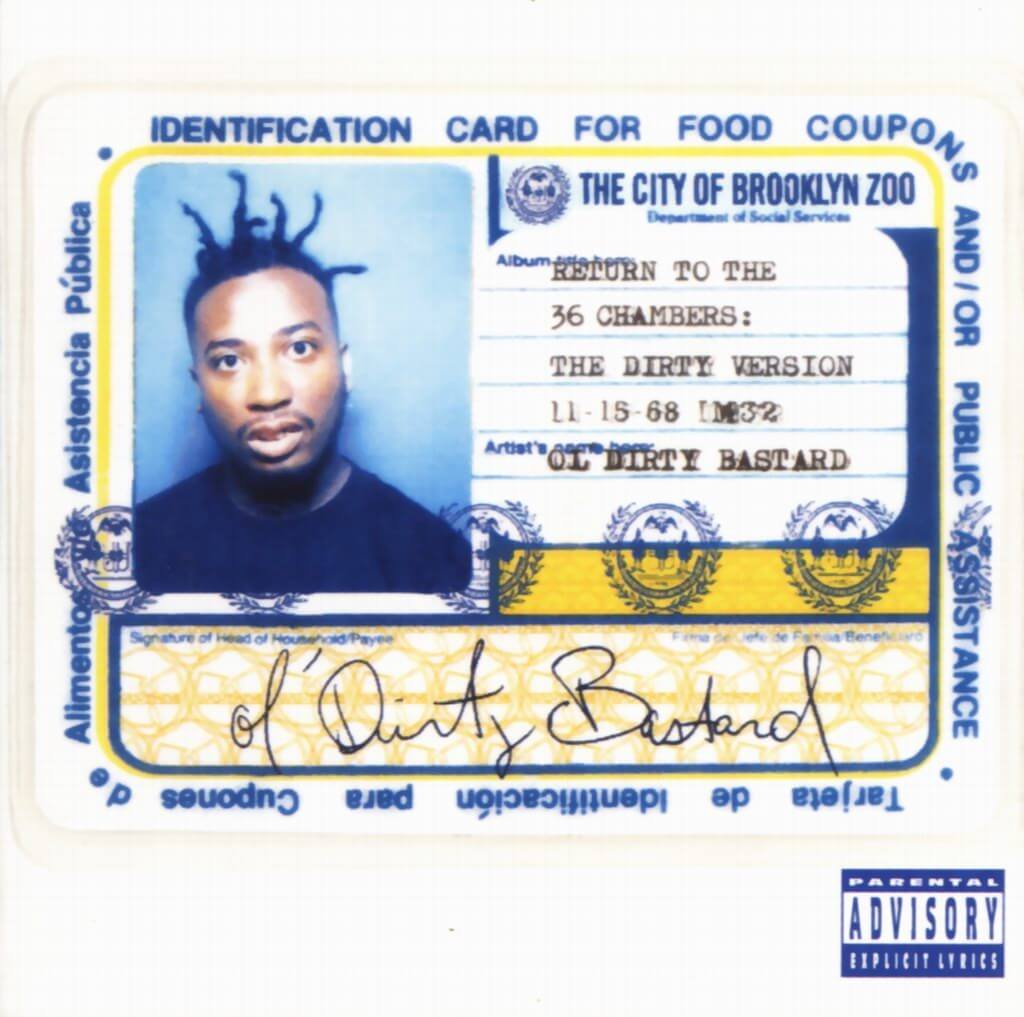

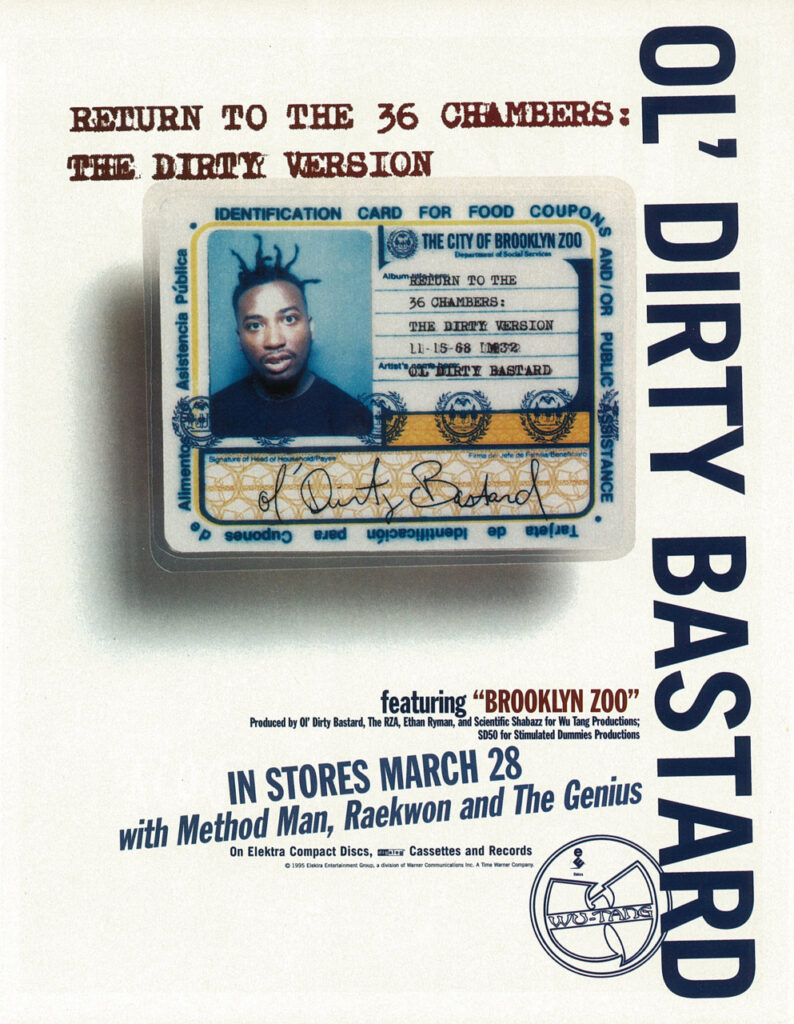

Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version is an album that throws you straight into the deep end of chaos. Released in 1995 as ODB’s first solo outing, it stands as one of Hip Hop’s most unapologetically raw and unhinged records. This is not music crafted for clarity or mass appeal—this is a dizzying descent into the world of Russell Jones, a man who performed under the moniker Ol’ Dirty Bastard and lived as though the rules simply didn’t apply to him.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Ol’ Dirty Bastard grew up alongside cousins RZA and GZA, two future members of the Wu-Tang Clan. Together, they laid the groundwork for a dynasty that would transform 1990s Hip Hop. While RZA became the mastermind behind Wu-Tang’s signature production and GZA was its cerebral storyteller and defacto leader, ODB carved out his place as the unpredictable wildcard. His delivery was erratic, half-sung and half-shouted, more about raw energy than technical precision. That energy takes center stage on Return to the 36 Chambers, a project that’s as much about ODB’s personality as it is about the music.

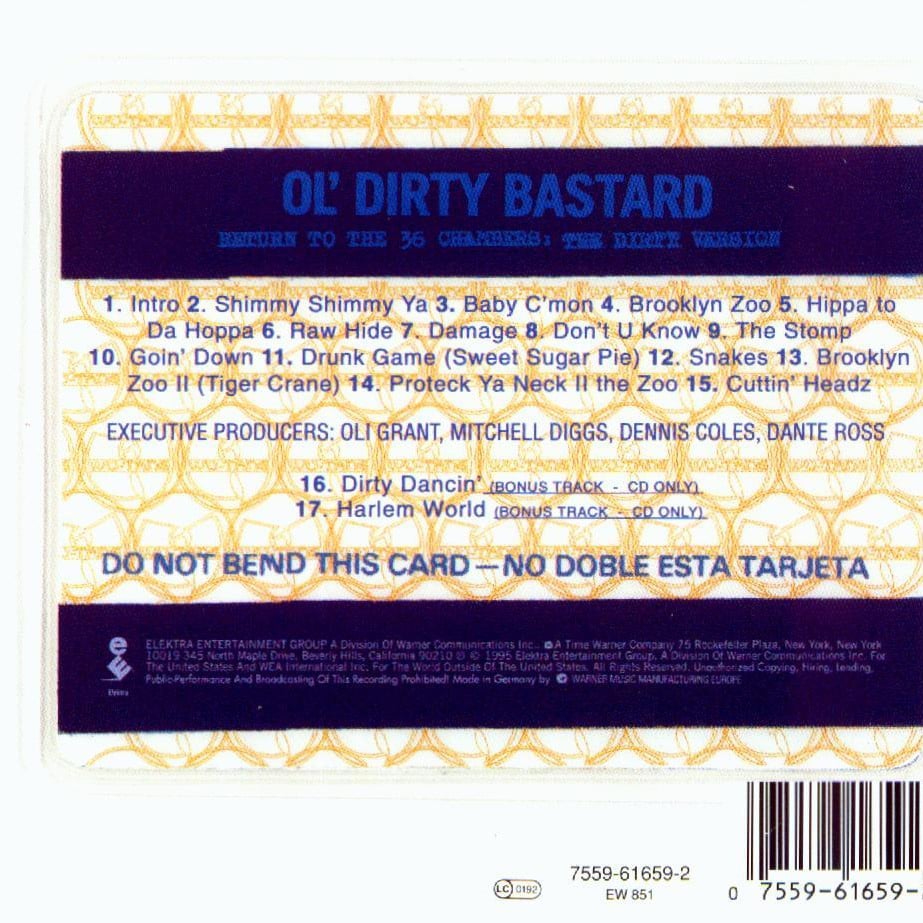

The album kicks off with a bizarre spoken-word intro, setting the tone for what’s to come. It feels less like an invitation and more like ODB barging into your living room, laughing wildly and demanding your full attention. The second track, “Shimmy Shimmy Ya,” is a perfect distillation of ODB’s charm. Over a piano loop that sounds like it was pulled from a dingy dive bar, ODB gleefully chants a hook that’s as nonsensical as it is infectious. His lyrics are simple, his cadence erratic, but it’s the way he owns the mic that makes the track impossible to ignore.

“Brooklyn Zoo,” the album’s first single, is even more aggressive. True Master’s gritty production is stripped down to its essence: heavy drums and a looping horn stab that feels claustrophobic in the best way. ODB delivers one relentless verse, spitting like he’s in the middle of a street brawl. The beat doesn’t offer much room to breathe, and ODB doesn’t need it—this is pure, untamed fury.

RZA, the album’s primary producer, doesn’t polish anything for commercial palatability. Instead, he crafts beats that sound like they’ve been pulled from a dusty basement and left to rot in the sun. Tracks like “Hippa to da Hoppa” and “Snakes” exemplify this approach, with unpredictable drum patterns and eerie melodies that underscore the madness ODB brings to the mic. The production is minimal but intentionally so, leaving space for ODB’s personality to fill the room.

What makes Return to the 36 Chambers so compelling is the way it embraces imperfection. There are moments where ODB’s slurred delivery stumbles over itself or his lyrics loop back on ideas already explored, but instead of detracting from the experience, these quirks add to its charm. On “Raw Hide,” for instance, Method Man and Raekwon deliver their verses with the polish and precision fans expect, but ODB’s off-kilter presence turns the track into something unpredictable. He’s not competing with his collaborators; he’s pulling them into his chaotic orbit.

One of the album’s standout tracks, “Cuttin’ Headz,” finds ODB trading verses with RZA. The two cousins go back and forth with a reckless energy that feels like a cipher happening in a crumbling apartment. The beat is skeletal—little more than drums and eerie atmospheric sounds—but it’s exactly the kind of backdrop ODB thrives on. He doesn’t need much to work with; his voice alone carries the weight.

That voice, though—what even is it? ODB doesn’t rap in the conventional sense. Sometimes he’s muttering like he’s three drinks in at a house party; other times, he’s wailing like he’s been kicked out of the club. Tracks like “Don’t U Know” and “Goin’ Down” show off his penchant for singing, though “singing” might not be the right word. His off-key crooning is messy, erratic, and unapologetically emotional. These are moments that remind you this album isn’t about technicality—it’s about capturing a vibe, however messy it might be.

While ODB is undeniably the star of the show, the album benefits from a strong supporting cast. Ghostface Killah, GZA, Method Man, and Raekwon all make appearances, lending their own distinct styles to tracks like “Damage” and “Brooklyn Zoo II.” Even when they bring a level of polish and lyrical precision, they can’t overshadow ODB’s presence. He’s not competing with them on their terms; he’s dragging them into his world of chaos.

That chaos, however, isn’t without its flaws. Tracks like “Drunk Game (Sweet Sugar Pie)” feel like experiments gone too far, where the lack of structure veers into outright incoherence. ODB’s freewheeling approach can sometimes feel self-indulgent, and there are moments where you wonder if anyone was actually in control of the recording sessions. But those missteps are part of what makes the album so fascinating—it’s a document of an artist who refused to play by the rules, even when those rules might have benefited him.

Return to the 36 Chambers isn’t an album you dissect for its lyrical content or its narrative structure. It’s an experience—a raw, visceral plunge into the mind of Ol’ Dirty Bastard. It’s messy, it’s loud, and it doesn’t care if you like it. ODB wasn’t trying to prove anything with this album; he was simply being himself, in all his unpredictable glory. In doing so, he created a record that feels alive in a way few others do.

At its core, this album is a reminder of the power of individuality in Hip Hop. ODB didn’t sound like anyone else because he couldn’t sound like anyone else. That’s what makes Return to the 36 Chambers endure: not its polish or its perfection, but its refusal to conform. It’s a snapshot of a moment in Hip Hop when anything felt possible, and Ol’ Dirty Bastard was leading the charge with a crooked grin and a bottle in hand.