New Orleans Hip Hop moves like the city it calls home—sweaty, rhythmic, and alive with history. It’s a sound that can trace its lineage to the same streets where brass bands parade through second lines and where call-and-response echoes from church pews to block parties. This is a place where music is lived. And that spirit courses through every bar, beat, and bassline of the city’s Hip Hop.

At its core, New Orleans Hip Hop is about movement—literal and figurative. In the early 1990s, bounce music burst from small clubs and neighborhood parties, fueled by frenetic tempos, local chants, and the endlessly versatile “Triggerman” beat. Tracks like MC T. Tucker and DJ Irv’s “Where Dey At” gave voice to the city’s wards and projects, turning a dancefloor callout into a communal anthem. Bounce wasn’t polished, and it wasn’t meant to be. It thrived in its rawness, bringing people together with a driving energy that felt uniquely New Orleans.

But the city’s rap scene didn’t stop at bounce. As the 1990s progressed, New Orleans became a hub for larger-than-life labels like No Limit Records and Cash Money Records, each staking their claim on the national stage with distinct styles. No Limit’s music hit like a tank, heavy and relentless, blending gangsta rap with streetwise hustle. Master P, Mia X, and Mystikal captured the grind and grit of their surroundings, while producers like Beats by the Pound layered tracks with the swampy, percussive pulse of the city.

Cash Money, on the other hand, carried the block party into the mainstream. Mannie Fresh’s beats bounced with bright, syncopated energy, while artists like Juvenile and Lil Wayne delivered charismatic flows that defined the Dirty South for a generation. Tracks like Juvenile’s “Back That Azz Up” turned regional rhythms into national anthems, and by the late 1990s, the city had become an undeniable force in Hip Hop.

Through hurricanes, tragedies, and upheaval, New Orleans Hip Hop has persisted. It’s adaptable, but its essence never strays far from the city’s roots. NOLA music carries the weight of its origins and the unshakable joy of its creators. These 25 albums tell that story—one of resilience, rhythm, and a sound unlike any other.

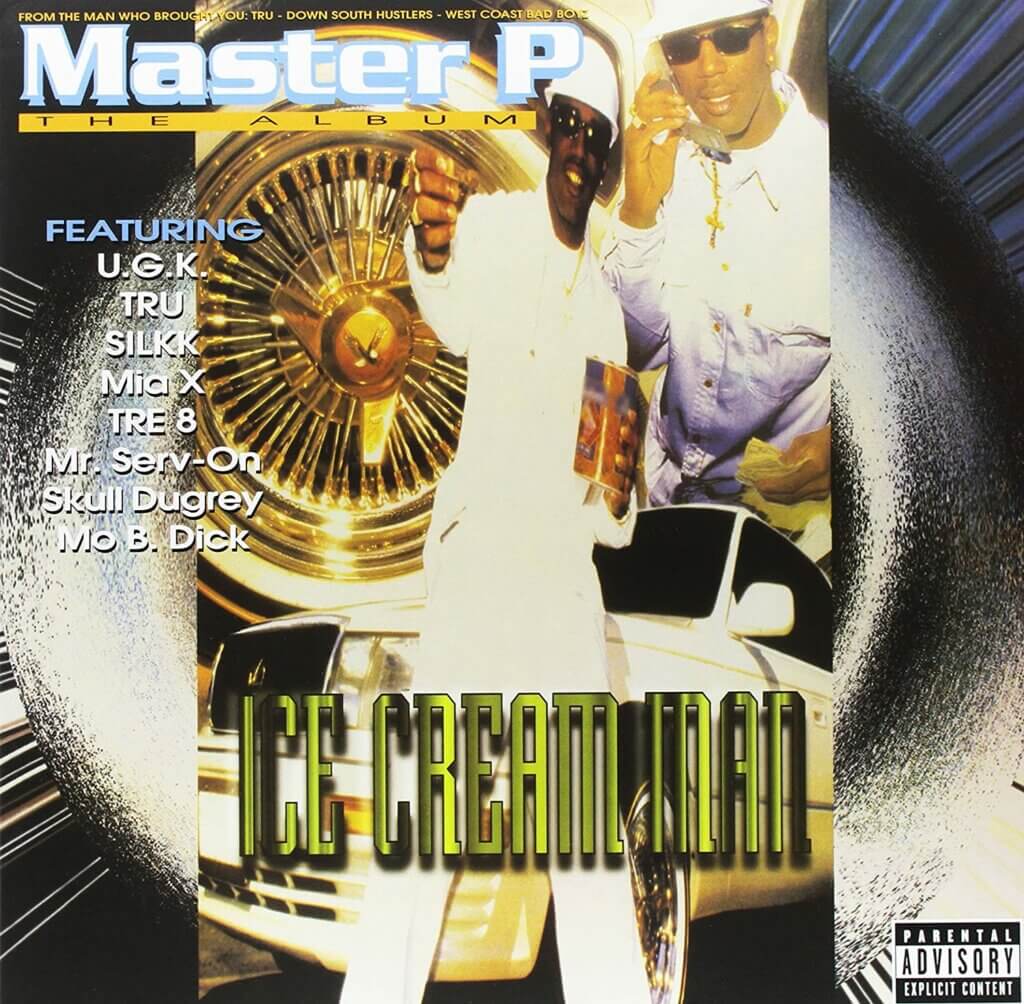

Master P - Ice Cream Man (1996)

Master P’s Ice Cream Man is the album that turned No Limit Records into a national powerhouse and introduced the gritty, unapologetic sound of New Orleans Hip Hop to a wider audience. While the production retains some traces of West Coast influence, it’s deeply rooted in Southern rap traditions, thanks in large part to the Beats by the Pound team, whose work on this album was nothing short of transformative.

The production is defined by thick, head-nodding basslines, slow-rolling drums, and eerie, atmospheric synths. Tracks like “Time for a 187” set a tense, cinematic tone, layering ominous keys over hard-hitting beats. The Al Green-sampling “The Ghetto Won’t Change” is a standout, offering a rare reflective moment on an album otherwise dominated by tales of street survival. The fusion of G-funk elements with Southern grit makes the album’s sound distinct, yet accessible—smooth enough to draw you in, but rugged enough to stay true to its roots.

Master P’s delivery is steady and conversational, often leaning on his ability to command a track with his presence rather than intricate lyricism. He isn’t a technical rapper, but his charisma and confidence make up for it. On “Bout It, Bout It II,” arguably the album’s defining anthem, his vocal swagger meshes perfectly with the track’s hypnotic groove, creating a song that feels both rebellious and celebratory.

The album’s themes revolve around the harsh realities of ghetto life, with a focus on hustling, violence, and survival. While Master P often revels in his role as a streetwise narrator, moments of introspection sneak in, adding layers to what might otherwise be dismissed as straightforward gangsta rap. Tracks like “Things Ain’t What They Used to Be” explore a weariness with street life, offering a glimpse of vulnerability beneath the bravado.

Clocking in at over 80 minutes, Ice Cream Man can feel overwhelming at times, and some tracks veer into filler territory. But for fans of ‘90s gangsta rap, the album’s sheer ambition and infectious production make it a compelling listen. It’s a snapshot of a rapper and label on the brink of superstardom, blending raw storytelling with beats that defined an era.

Mia X – Unlady Like (1997)

Mia X’s Unlady Like, released in 1997 on No Limit Records, presents a complex picture of Southern Hip Hop at the time. The album, a lengthy offering clocking in at around 80 minutes, is steeped in the signature sound of the label’s in-house production team, Beats By the Pound. This sonic backdrop is characterized by heavy bass, often distorted and rumbling, with simple, repetitive melodic loops. It creates a dark, gritty atmosphere, fitting for the album’s themes of street life and survival.

The album opens with tracks like “You Don’t Wanna Go 2 War,” featuring TRU and Mystikal. The production here is dense, the bass prominent, and Mia X’s delivery is assertive, her thick Southern drawl cutting through the mix. The mood is confrontational, setting the stage for much of what follows. Tracks like “The Party Don’t Stop,” with Master P and Foxy Brown, offer a slight change of pace. While still rooted in the No Limit aesthetic, this track has a more upbeat feel, driven by a slightly lighter, more danceable rhythm.

Mia X’s vocal presence is a defining characteristic of the album. Her voice is commanding, adding weight to her lyrics. On tracks like the title track, “Unlady Like,” her flow is rhythmic and precise, navigating the beat with confidence. The production, handled by KLC on this track, is more stripped down, allowing her voice to take center stage.

The album’s structure is typical of No Limit releases of the era, with numerous guest appearances. While these features provide variety, they sometimes disrupt the album’s flow. There are moments, such as on “Mama’s Family,” featuring a large ensemble of No Limit artists, where the track feels crowded, with each verse vying for attention.

However, Unlady Like also contains moments of genuine depth. Tracks like “I Don’t Know Why,” “Mommie’s Angels,” and “RIP, Jill” offer a more introspective side to Mia X, dealing with themes of loss, struggle, and personal reflection. On these tracks, the production, often handled by Mo B. Dick, takes on a more melancholic tone, with slower tempos and more subdued instrumentation. These moments provide a contrast to the more aggressive tracks, adding emotional complexity to the album. While the album’s length and some uneven production choices affect its overall impact, Unlady Like offers a valuable glimpse into Mia X’s artistry and the sound of New Orleans Hip Hop in the late 90s.

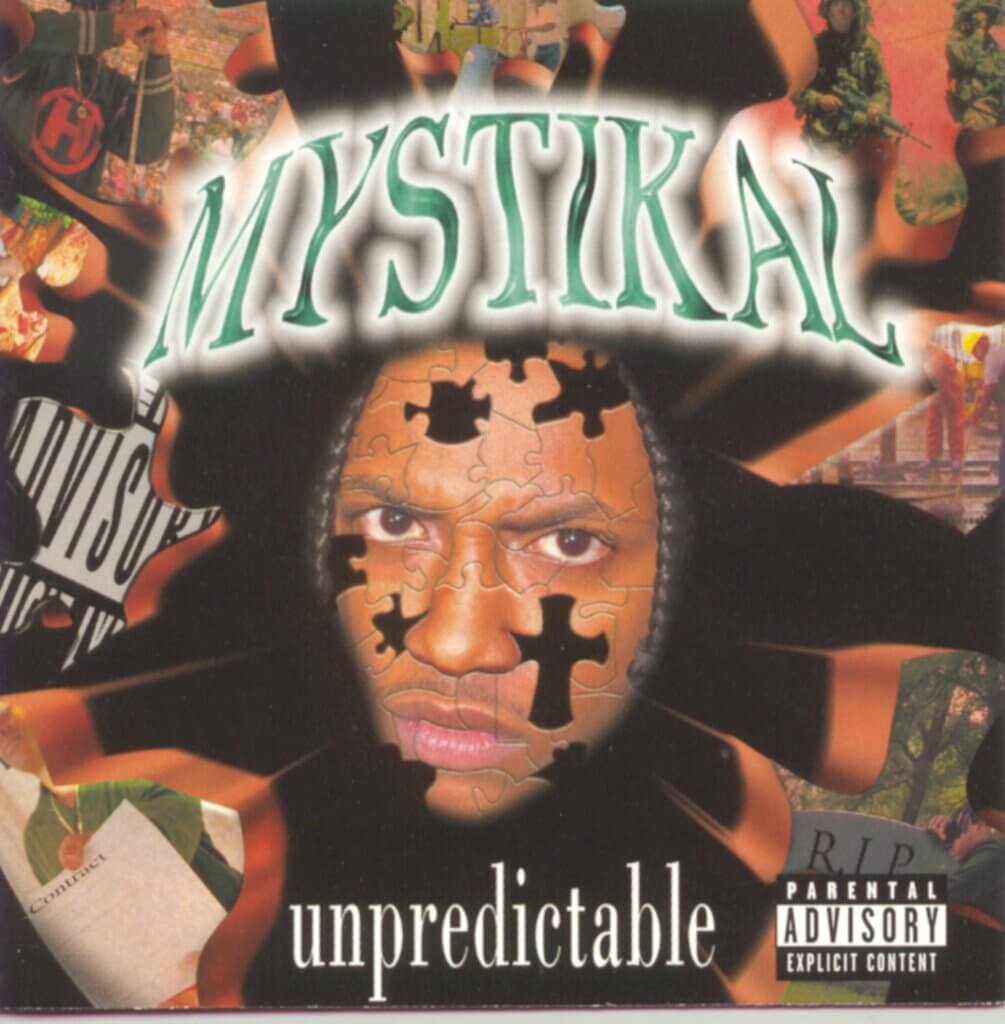

Mystikal - Unpredictable (1997)

Mystikal’s Unpredictable, his 1997 No Limit Records debut, is a chaotic burst of energy contained within a roughly 70-minute runtime. The album is a product of its time and label, featuring the characteristic heavy bass and simplistic loops of Beats By the Pound, but it’s Mystikal’s distinct vocal delivery that truly defines the project. His style is frantic, often delivered at a rapid-fire pace, with a thick Southern drawl and a tendency to shout or yell certain phrases for emphasis. This creates a sense of urgency and intensity throughout the album.

The production, while consistent with the No Limit sound, varies in quality. Some tracks, like “Ain’t No Limit,” have a driving, energetic feel, with booming bass and a catchy hook. Others, however, rely on simpler loops that, while effective in creating a dark, street-oriented atmosphere, can become repetitive over the course of the album. The album’s structure, with its frequent guest appearances, is also a mixed bag. While features from artists like E-40, Snoop Dogg (credited as Snoop Doggy Dogg), and several No Limit Soldiers add variety, they sometimes disrupt the album’s momentum.

Mystikal’s lyrical content on Unpredictable focuses primarily on street life, violence, and his own lyrical abilities. He often employs vivid imagery and boasts about his skills with a mix of humor and aggression. On tracks like the title track, “Unpredictable,” his delivery is particularly animated, his voice fluctuating between a rapid-fire flow and shouted pronouncements. The mood here is one of controlled chaos, reflecting the unpredictable nature of the streets he describes.

Despite the album’s aggressive tone, there are moments of reflection. “Shine,” the closing track, offers a poignant dedication to Mystikal’s sister. The production here is more subdued, with a somber melody and a slower tempo, creating a stark contrast to the rest of the album. This track provides a glimpse into a more personal side of Mystikal, adding emotional depth to the project.

While the album’s length and some uneven production choices affect its overall consistency, Unpredictable offers a compelling look at Mystikal’s unique style and the sound of No Limit Records at its commercial peak. His energetic delivery and distinct vocal presence make this album a noteworthy entry in New Orleans Hip Hop history.

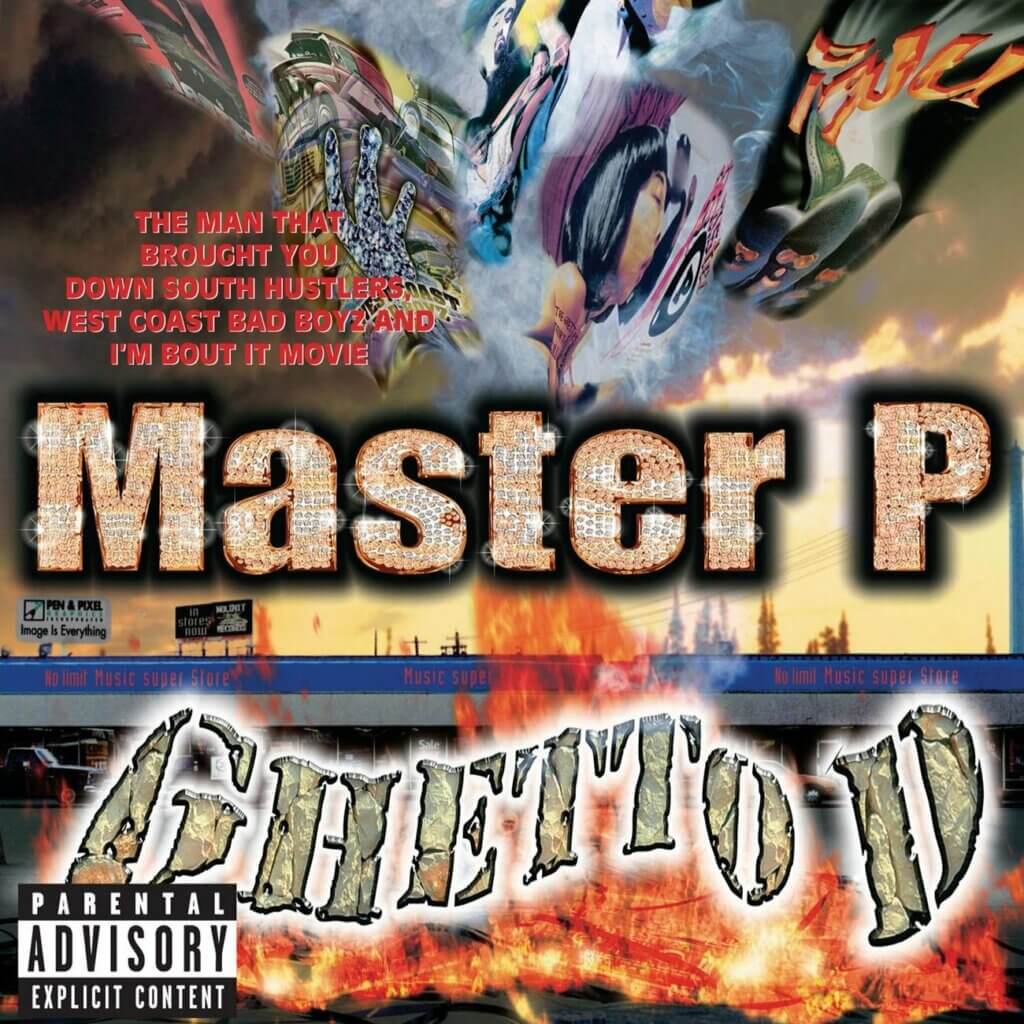

Master P - Ghetto D (1997)

Master P’s Ghetto D is a sprawling, audacious declaration of the No Limit Records ethos: bigger, louder, and totally over the top. Released in 1997, this 80-minute opus doesn’t try to cater to purists or critics. Instead, it immerses itself in the realities and fantasies of street life, delivered with a blunt-force approach that makes it as addictive as the metaphorical crack referenced in its opening track.

From the start, Ghetto D leans into its aggressive identity. The title track reimagines Eric B. & Rakim’s classic “Eric B. Is President,” swapping out its clever, feel-good energy for the raw mechanics of the drug trade. It’s not subtle, and it’s not meant to be. This directness defines the album. Tracks like “Make ‘Em Say Uhh!” are built on anthemic hooks, stomping beats, and Master P’s guttural ad-libs, turning simplicity into a virtue. Mystikal’s fiery delivery on the posse cut steals the show, but P’s presence—gritty, unpolished, and undeniably magnetic—holds the chaos together.

The album operates more like a compilation than a solo project. Master P surrounds himself with the No Limit roster, creating a rotating cast of characters that keep the album moving at a relentless pace. Mia X’s confident delivery on “Plan B” offers balance, while Fiend and Silkk the Shocker bring a range of energy to tracks like “Tryin 2 Do Something” and “I Miss My Homies.” The latter, a somber reflection on loss, rides a soulful interpolation of The O’Jays’ “Brandy” and softens the album’s otherwise hard edges, showing No Limit’s ability to blend vulnerability with bravado.

The production by Beats By The Pound elevates Ghetto D. Bass-heavy, minimalist beats provide the backbone, marrying Southern bounce with a pop sensibility. Tracks like “Bourbons and Lacs” exemplify this, pairing Marvin Gaye-inspired melodies with booming 808s. It’s glossy and raw at the same time, a sound that would become the blueprint for Southern Hip Hop’s takeover in the years to come.

Ghetto D isn’t polished or introspective; it’s indulgent, unfiltered, and designed for impact. Its sheer audacity and its role in popularizing Southern rap’s commercial rise make it an essential chapter in Dirty South history. Whether you love it or hate it, Ghetto D is impossible to ignore.

TRU - TRU 2 da Game (1997)

TRU 2 da Game is a LONG double album that encapsulates the sound and ethos of No Limit Records in its heyday. Made up of Master P, C-Murder, and Silkk the Shocker, TRU delivers a mix of gritty gangsta tales, braggadocious anthems, and a few introspective moments across more than two hours of music. While the sheer length can be overwhelming, the album captures a raw energy that was central to the rise of Southern Hip Hop in the late ‘90s.

The production, handled by the No Limit in-house team Beats By the Pound, leans heavily into booming 808s, eerie synth lines, and minimal melodies that give the tracks a dark, menacing edge. Songs like “No Limit Soldiers” and “I Always Feel Like” ride hypnotic basslines and haunting hooks, creating the kind of anthems that defined the No Limit sound. “Heaven 4 a Gangsta,” with its reflective tone, stands out for its more introspective lyrics, while tracks like “Ghetto Thang” and “Swamp Nigga” paint vivid pictures of life in the streets.

Master P’s gruff delivery, C-Murder’s steely flow, and Silkk’s offbeat, unpredictable cadence form a distinct dynamic. While none of them are the most technically skilled lyricists, their commanding presence and regional authenticity carry much of the material. C-Murder, in particular, brings a colder, more understated energy that balances Master P’s larger-than-life persona. Silkk’s erratic style can be divisive—at times adding a frenetic energy, at others feeling clumsy.

At over two hours, the album does drag in places, with repetitive themes and occasional filler tracks like “Freak Hoes” breaking the momentum. Still, there are enough standout moments to hold attention, especially for fans of Southern gangsta rap. The mix of storytelling tracks and harder, club-ready bangers keeps the album from becoming completely monotonous.

TRU 2 da Game is emblematic of No Limit’s approach during their peak: relentless output, a do-it-yourself aesthetic, and an unapologetic Southern swagger. Though not without its flaws, it’s an essential listen for anyone looking to understand the era and its influence on Hip Hop culture.

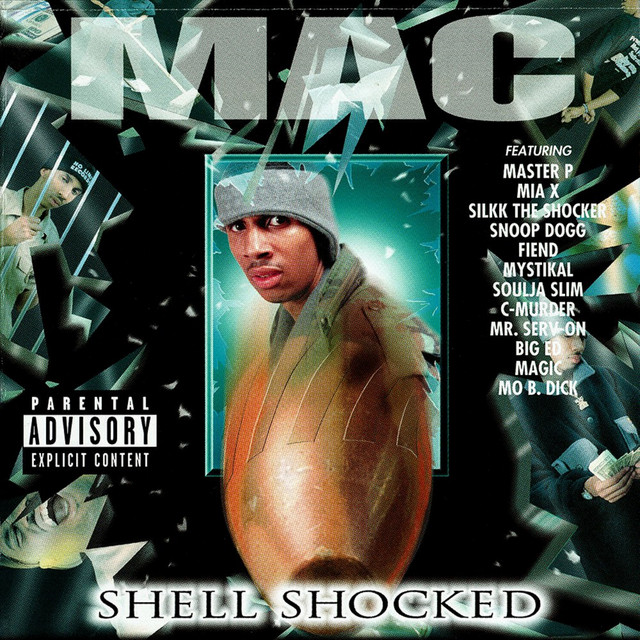

Mac - Shell Shocked (1998)

Mac’s Shell Shocked is a cornerstone of No Limit Records’ legendary late ‘90s run, delivering 21 tracks of southern Hip Hop that reflect Mac’s lyrical precision and storytelling prowess. Anchored by Beats By The Pound’s production, the album blends the label’s signature bounce with Mac’s deeply personal and sharp lyrical style, resulting in one of the most distinctive releases from No Limit’s prolific catalog.

From the opening moments, Mac establishes himself as a skilled storyteller. Tracks like “Slow Ya Roll” unravel coming-of-age struggles, while “Paranoid” dives into the psyche of a man consumed by fear and survival. Mac’s delivery is deliberate—his voice carries weight, not just in tone but in content. He shifts between vivid street narratives and introspective reflections, capturing a complex spectrum of emotion. In “My Brother,” Mac’s heartfelt dedication hits especially hard, balancing raw vulnerability with a sense of resilience.

The production matches Mac’s intensity, with Beats By The Pound crafting a sound that’s simultaneously gritty and melodic. Tracks like “Tank Dogs” and “Murda, Murda, Kill, Kill” bring in heavy basslines and frenetic energy, while “Callin Me” slows things down with a soulful hook, albeit veering into more commercial territory. The beats stay diverse but cohesive, each track carrying its own identity without straying from the album’s southern foundation.

Mac’s collaborations add depth to the album without overshadowing him. Fiend’s deep growl complements Mac on tracks like “Be All You Can Be” and “Shell Shocked,” while Mystikal’s fiery energy ignites “Murda, Murda, Kill, Kill.” Even Master P, often criticized for his verses, contributes effectively on “Soldier Party.” That said, the album’s length—a common No Limit issue—leads to moments of filler, with tracks like “Meet Me At The Hotel” and “Camouflage Love” feeling less impactful.

Despite these minor dips, Shell Shocked thrives on its lyrical depth, varied production, and Mac’s magnetic presence. It is a testament to his underrated brilliance, offering a raw and resonant snapshot of New Orleans Hip Hop during its golden era. For fans of No Limit or southern rap, it’s an essential listen, marking Mac as one of the label’s most gifted artists.

Tragically, Mac’s career was cut short not by lack of talent but by circumstances outside the music. In 2001, Mac was convicted of manslaughter after a nightclub shooting in Slidell, Louisiana—a conviction widely criticized for its lack of evidence and questionable testimony. Sentenced to 30 years to life, Mac became a victim of a justice system that many argue unfairly targeted him. His incarceration not only halted a promising career but also underscored the systemic issues faced by Black men in America. Though Shell Shocked hinted at his great potential, Mac’s story remains one of Hip Hop’s most heartbreaking examples of talent derailed by legal injustice.

C-Murder – Life Or Death (1998)

C-Murder’s Life or Death is an unmistakably dark and relentless project that reflects the grit of New Orleans’ streets while exemplifying No Limit Records’ distinctive late-’90s sound. Spanning a hefty 26 tracks, the album is steeped in tales of violence, survival, and street loyalty, delivered with a raw conviction that gives C-Murder his edge. While it doesn’t aim for introspection or lyrical complexity, the album thrives on its visceral energy and atmospheric production.

The record opens with anthems like “A 2nd Chance” and “Akickdoe!” where C-Murder’s deep, gruff delivery is bolstered by Beats by the Pound’s booming basslines and layered synths. The production team, essential to the No Limit aesthetic, crafts instrumentals that are both heavy and unrelenting, matching the album’s grim tone. Songs such as “Feel My Pain” and “Ghetto Ties” lean into slower, more reflective tempos, with haunting melodies that underscore the weight of C-Murder’s narratives. His vocal delivery, influenced by 2Pac’s cadence, carries an unpolished charisma that fits the unapologetically harsh content.

However, the album’s sheer length and thematic repetition make it a challenging listen in one sitting. The guest features, including Mystikal, Mia X, and Mac, provide some variety, but many tracks feel interchangeable, circling back to the same gritty motifs of street violence and retribution. While C-Murder’s flow is consistent, he rarely steps out of his comfort zone, sticking to a single gear throughout the record.

That said, Life or Death succeeds in its purpose—it’s an unfiltered snapshot of the Third Ward’s realities, delivered with an authenticity that resonates with fans of Southern gangsta rap. Despite its flaws, the album holds a firm place in No Limit’s catalog, a reflection of the label’s dominance during this era. Tracks like “Soldiers” and “Cluckers” stand out as highlights, embodying the relentless drive that defined both C-Murder and the No Limit movement. If nothing else, Life or Death is a testament to the raw, unvarnished storytelling that made this era of Hip Hop unforgettable.

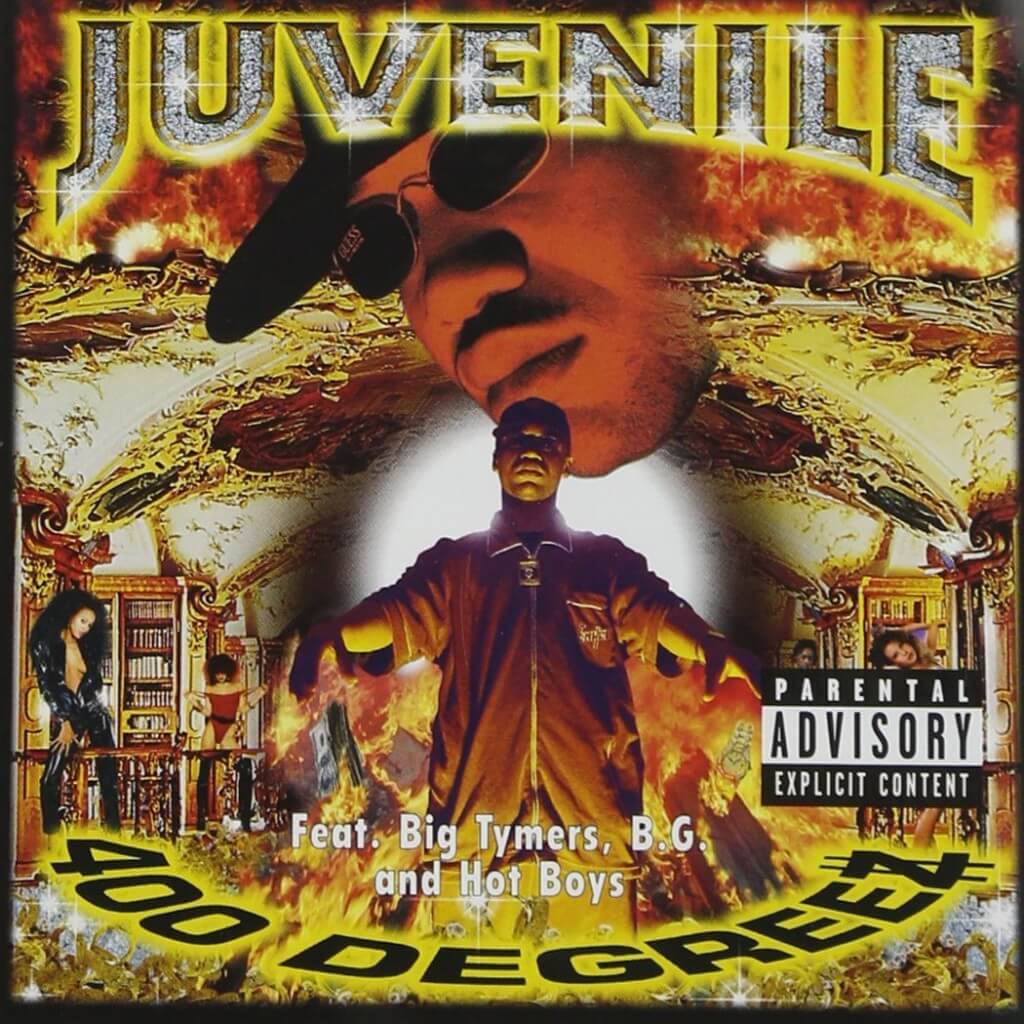

Juvenile – 400 Degreez (1998)

Juvenile’s 400 Degreez dropped like a Molotov cocktail into the late-’90s Hip Hop scene. With Mannie Fresh’s hypnotic production and Juvenile’s raw, conversational delivery, this album helped propel New Orleans rap into national prominence. It wasn’t polished or overly technical; instead, it drew its power from the city’s bounce-heavy rhythms and Juvenile’s ability to make you feel like you were sitting on a stoop in the Magnolia Projects, hearing stories from someone who lived it all.

The production on 400 Degreez feels alive, teeming with skittering hi-hats, basslines that punch, and Mannie Fresh’s knack for layering melodies that get stuck in your head after one listen. Tracks like “Ha” thrive on this simplicity. Over a looping, almost taunting beat, Juvenile peppers the listener with second-person accusations and observations—about money, loyalty, and the pitfalls of street life. The repetition of “Ha” after every line hooks you, turning mundane reflections into something urgent and biting. The remix featuring Jay-Z gives the track a broader appeal, but it’s Juvenile’s drawl that stays with you.

“Back That Azz Up” is the undeniable centerpiece, an anthem with such kinetic energy it became a cultural phenomenon. From the orchestral string intro to the explosive beat drop, the song refuses to let you stay still. Juvenile’s swagger oozes through the track, while Mannie Fresh crafts a party record that defined dance floors across the South and beyond.

The album’s lesser-known tracks build a fuller picture of Juvenile’s world. “Ghetto Children” offers a sobering reflection on systemic struggles, while “Rich N****z” explodes with brash confidence over Mannie’s dynamic beat changes. Juvenile’s verses balance humor, anger, and vulnerability, delivered in a cadence that’s unique to his corner of New Orleans.

What 400 Degreez does better than anything else is stay rooted in its sense of place. The language, the attitude, and the rhythms are unmistakably New Orleans. Juvenile’s drawl bends and stretches words into shapes that feel as distinct as the beats underneath them. It’s an album that doesn’t try to be everything for everyone but instead invites the listener into its world. By the time it closes, you’re left with a body of work that cemented Cash Money Records as a force and Juvenile as a storyteller who could make the ordinary feel monumental.

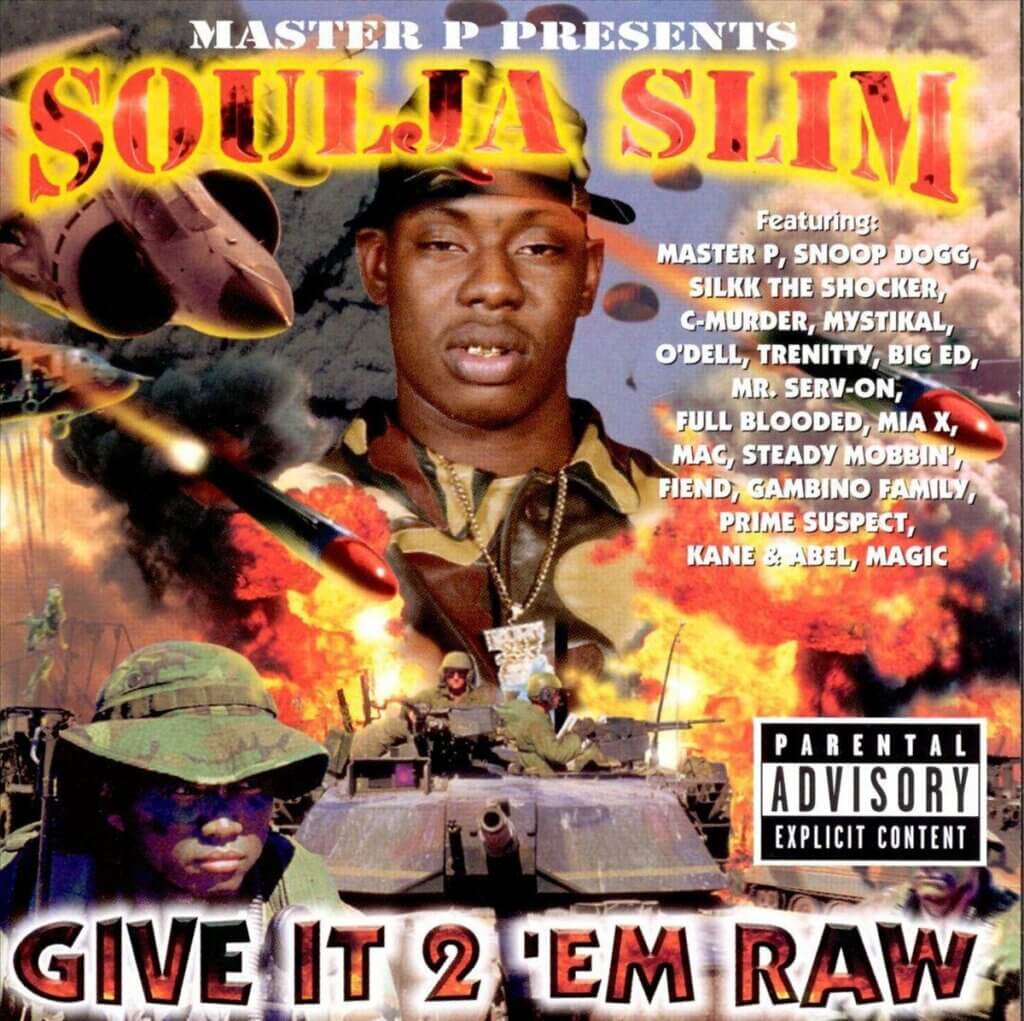

Soulja Slim - Give It 2 'Em Raw (1998)

Soulja Slim’s Give It 2 ‘Em Raw is a quintessential slice of late-90s New Orleans Hip Hop—gritty, relentless, and soaked in the intensity of Slim’s Magnolia Projects upbringing. Released through Master P’s No Limit Records during its peak, the album thrives on Beats by the Pound’s signature production: an ominous yet vibrant mix of heavy basslines, rattling hi-hats, and eerie synths that capture the chaotic energy of the streets Slim rapped about.

From the opening track, “From What I Was Told,” Slim’s delivery is unfiltered and direct, his voice carrying a thick southern drawl that oozes authenticity. The beat explodes with gunshot sound effects and a menacing digital edge, perfectly setting the tone for Slim’s relentless storytelling. The album rarely lets up, offering track after track of raw street narratives, like the brutally honest “You Ain’t Never Seen,” where Slim chronicles a life scarred by addiction, incarceration, and survival in one of New Orleans’ most notorious housing projects.

At 20 tracks long, Give It 2 ‘Em Raw feels like a marathon session of Slim purging his demons onto tape. Songs like “Wright Me” and “Only Real Niggas” delve deep into his experiences, balancing personal reflection with unapologetic aggression. His flow is rugged and unpolished, yet his presence is undeniable. Tracks like “Head Buster” and “What’s Up What’s Haapening” showcase Slim’s ability to switch between mournful introspection and defiant bravado, often within the same verse. His verses are personal and deeply tied to his environment, a form of street journalism that spares no detail.

Guest appearances from the No Limit roster, including C-Murder, Silkk the Shocker, and Fiend, add variety, though Slim remains the focal point. Mia X shines on the duet “Anything,” offering a sharp contrast to Slim’s gruff delivery. The production remains consistent throughout, with Beats by the Pound crafting instrumentals that are atmospheric yet hard-hitting—perfect backdrops for Slim’s intense style.

Soulja Slim’s life came to a tragic end on November 26, 2003, when he was shot multiple times in front of his mother’s home in the Gentilly neighborhood of New Orleans. He was 26 years old. The loss of Slim is felt deeply in Give It 2 ‘Em Raw, as the album already carries the weight of a young man grappling with the harsh realities of street life. Slim’s unflinching honesty and raw energy hint at an artist with even more to give, making his untimely death feel like the silencing of a voice that hadn’t fully realized its potential.

While the album’s mix can feel dated, with its occasionally muddy sound and cluttered arrangements, it adds to the rawness that defines the record. Give It 2 ‘Em Raw is a time capsule of New Orleans street rap, an album that places you in the heart of Slim’s world, chaotic and unfiltered. It’s this unvarnished honesty, coupled with the tragedy of his short life, that continues to make the album a vital entry in Southern Hip Hop history.

Fiend — There’s One in Every Family (1998)

Fiend’s There’s One in Every Family is another strong No Limit album, balancing the label’s signature bombast with moments of introspection and Fiend’s unmistakable gravelly voice. Across its sprawling 80-minute runtime, Fiend delivers a versatile performance, moving between explosive energy and soulful reflection, anchored by Beats by the Pound’s rich, hard-hitting production.

The album opens unexpectedly with “Take My Pain,” a somber track that sees Fiend reflecting on loss and survival. It’s a haunting introduction, with mournful keys and a hook delivered by Master P that sets a reflective mood before the record plunges into more aggressive territory. From there, Fiend’s commanding presence takes over on tracks like “Talk It How I Bring It” and “Big Timer,” where his hoarse, guttural delivery cuts through the thunderous basslines and rattling hi-hats. His vocal style—a mix of raw intensity and melodic inflection—adds weight to every line, whether he’s rapping about street life or flexing his dominance.

Beats by the Pound crafts an expansive sonic palette for the album. Tracks like “For the N.O.” ride on eerie synth melodies and booming percussion, while songs like “Going Out with a Blast” bring frenetic energy with their rapid drum patterns and hypnotic hooks. The production stays rooted in the classic No Limit sound—layered, menacing, and bass-heavy—while leaving space for Fiend’s charismatic flow. His ability to adapt his style keeps the lengthy tracklist engaging, switching from aggressive battle cries to slower, introspective moments like “Only a Few.”

Guest features are plentiful, with No Limit stalwarts like Master P, Mystikal, and Silkk the Shocker contributing verses that enhance the collaborative energy of the album. Mystikal’s fiery delivery on “Who Got the Fire” contrasts sharply with Fiend’s gruff tone, creating a standout moment.

Though There’s One in Every Family can feel bloated at times, its high-energy tracks and moments of genuine emotion make it an essential entry in the No Limit catalog and a standout of New Orleans Hip Hop in the late ‘90s. Fiend’s raw intensity and Beats by the Pound’s thunderous production ensure the album’s place as a defining record of the era.

Silk The Shocker — Charge It 2 Da Game (1998)

Silkk The Shocker’s Charge It 2 Da Game is a polarizing entry in No Limit Records’ prolific catalog, reflecting the label’s peak commercial success while showcasing Silkk’s unconventional rap style. With its mix of high-energy anthems and introspective tracks, the album offers a snapshot of the late ’90s Southern Hip Hop era, powered by Beats by the Pound’s booming production.

The album kicks off with “I’m a Soldier,” a thunderous opener that sets the aggressive tone, built on pounding drums and militaristic chants. Silkk’s offbeat delivery—characterized by his tendency to rush or lag behind the beat—makes him stand out, though most of the times not in a good way. Tracks like “It Ain’t My Fault,” featuring Mystikal, are undeniable highlights, with Mystikal’s ferocious energy grounding the chaos of Silkk’s scattershot flow. The contrast between the two rappers creates an electric dynamic, amplified by the track’s pounding rhythm and catchy hook.

Production throughout the album leans heavily on No Limit’s signature sound: booming 808s, dramatic strings, eerie synth lines, and crisp snares. Beats by the Pound excels on tracks like “Let Me Hit It,” a club-ready anthem, and “Me and You,” which tones down the intensity with a more reflective, storytelling approach. Silkk shifts gears here, recounting a personal narrative with a sincerity that breaks through the bravado found on much of the album.

While Charge It 2 Da Game has strong moments, its length works against it. At 79 minutes, the album drags, with filler tracks diluting the impact of standout cuts. Silkk’s lack of technical polish as a rapper becomes more evident on weaker songs, where his unorthodox flow and inconsistent energy can feel grating rather than engaging.

Despite its flaws, Charge It 2 Da Game is an essential piece of No Limit’s legacy, capturing the peak of the label’s dominance in the late ’90s. With its mix of chart-topping singles, raw energy, and nostalgic Southern production, it remains a divisive but memorable release in New Orleans Hip Hop.

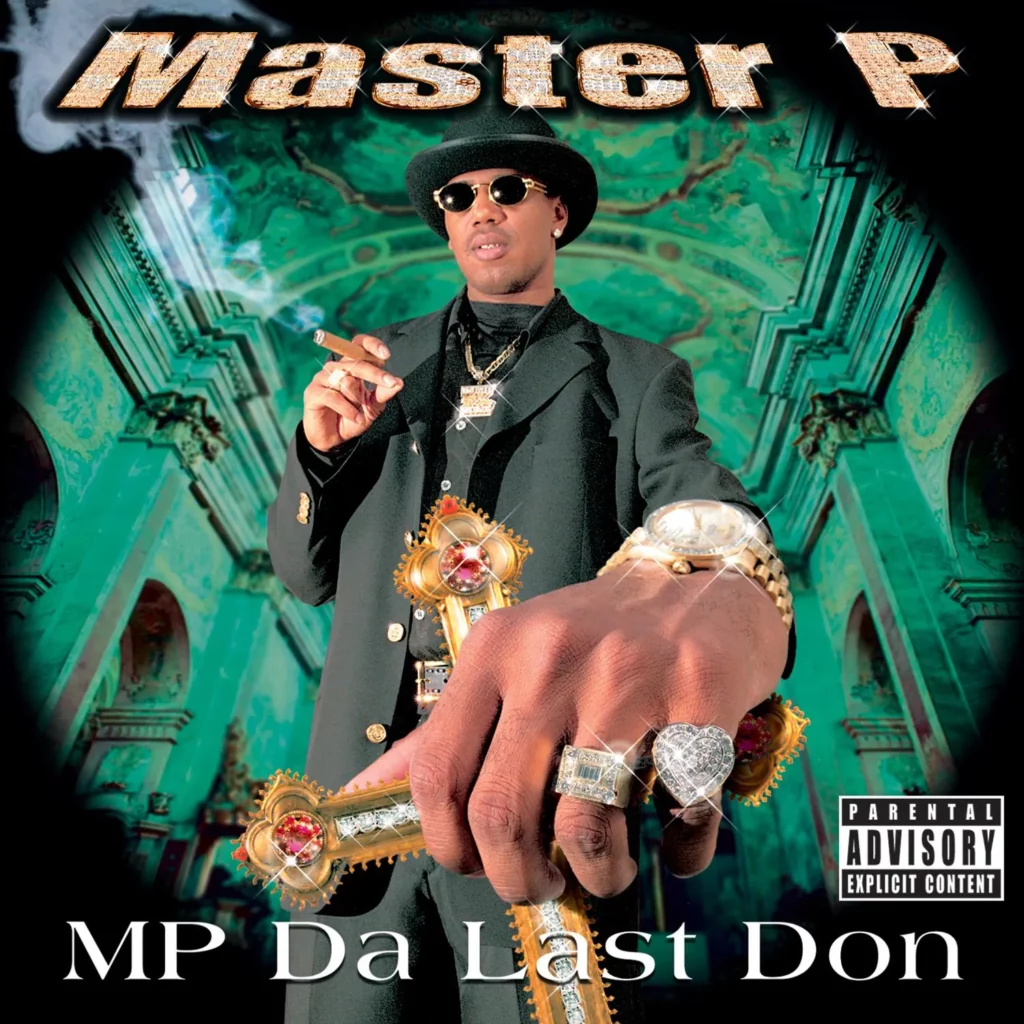

Master P — MP Da Last Don (1998)

Master P’s MP Da Last Don is a bold, sprawling album that captures the height of No Limit Records’ reign in 1998. Billed as his retirement record (a claim quickly abandoned), this double-disc release spans across 29 tracks and over 100 minutes, combining booming Southern production, aggressive lyrics, and an unapologetic flex of No Limit’s dominance. It’s not a flawless album, but its ambition and context make it unforgettable.

The standout feature of MP Da Last Don is the production from Beats by the Pound, No Limit’s in-house collective that defined the label’s sound. The beats are heavy on bass, sharp synths, and rattling hi-hats, creating a relentless Southern groove that blurs the line between funk and menace. Tracks like “Get Your Paper,” featuring E-40, and “War Wounds,” a fiery posse cut with Mystikal, Fiend, and Silkk the Shocker, hit with raw energy and serve as the album’s core. The beats shift effortlessly between stomping street anthems and cinematic nods to 1970s Blaxploitation soundtracks, with wah-wah guitars and moody arrangements that evoke pulp gangster vibes.

Lyrically, Master P stays in his comfort zone. He’s never been the most complex writer, leaning on straightforward bars about hustling, loyalty, and survival. His booming delivery, however, carries an emotional weight that transcends his limitations as a lyricist. On tracks like “More 2 Life” and “Ghetto Life,” his frustration and pain feel palpable as he reflects on systemic oppression and personal struggles. That rawness falters on attempts at political commentary, such as “Dear Mr. President,” where vague critiques of global politics come across as clumsy rather than insightful.

The album’s biggest flaw is its length. With 29 tracks, some feel unnecessary or redundant, especially filler like “Thug Girl” and the repetitive interludes. Yet, the sheer volume is a reflection of No Limit’s approach at the time—dominate the market with content and give fans their money’s worth.

Ultimately, MP Da Last Don represents a pivotal moment in Hip Hop and Southern rap. It’s a loud, chaotic celebration of No Limit’s empire, driven by ambition, excess, and the unrelenting grind that Master P built his brand on. While imperfect, the album’s energy and cultural significance remain undeniable.

B.G. - Chopper City In The Ghetto (1999)

B.G.’s Chopper City in the Ghetto, released in 1999, arrived during Cash Money Records’ ascendance, following Juvenile’s breakthrough with 400 Degreez. This album, entirely produced by Mannie Fresh, is a prime example of the label’s distinctive sound during this period. The music is characterized by heavy bass, often with a pronounced 808 kick, layered with intricate keyboard melodies and a bounce-influenced rhythm. This creates a hard-hitting but danceable sound, fitting for the album’s themes of street life and material success.

The album opens with an intro featuring Baby and Mannie Fresh, establishing the Cash Money aesthetic with their signature slang and boasts. This leads into tracks like “Trigga Play,” where B.G.’s delivery is direct and assertive, his rhymes painting vivid pictures of street encounters. The production here is dense and energetic, with a driving beat that propels the track forward.

“Cash Money Is an Army” functions as a crew anthem, with B.G. declaring his loyalty and affiliation. The beat has a celebratory feel, with a catchy hook and a prominent bassline. This track, along with others like “Made Man,” emphasizes the Cash Money collective and their rise to prominence.

The album also includes “Bling Bling,” a track that had a significant impact on popular culture, introducing the term into mainstream lexicon. The song has a party atmosphere, with a catchy chorus and verses from B.G., Big Tymers, and the Hot Boys. The production is bright and energetic, contributing to the song’s widespread appeal.

However, Chopper City in the Ghetto is not solely focused on celebratory themes. Tracks like “Hard Times” offer a more introspective look at B.G.’s past, describing the struggles and challenges he faced growing up. The production on this track is more subdued, with a somber melody that reflects the song’s reflective mood.

The album’s structure, typical of Cash Money releases, includes numerous guest appearances from labelmates like Juvenile, Lil Wayne, Turk, and the Big Tymers. These features add variety to the album, with each artist bringing their own distinct style and flow. While some tracks, like “Dog Ass,” contain content that might be considered controversial, they reflect the prevalent themes within the genre at the time.

Overall, Chopper City in the Ghetto provides a snapshot of Cash Money’s sound and influence at the close of the 20th century. B.G.’s delivery, combined with Mannie Fresh’s production, creates an album that is both a product of its time and a significant entry in New Orleans Hip Hop history.

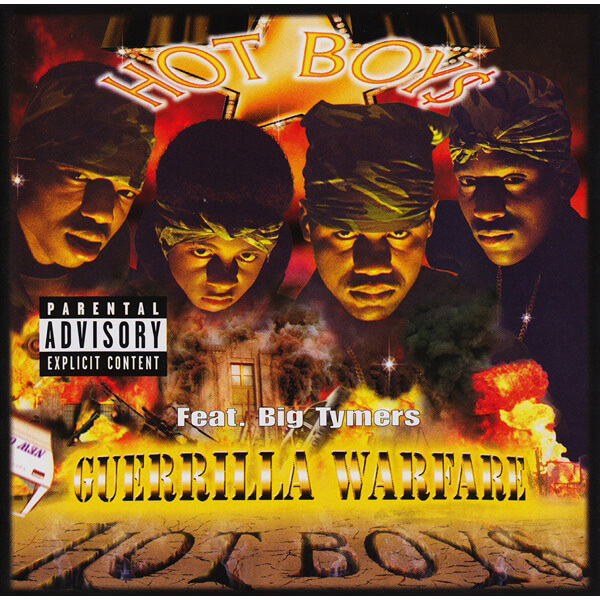

Hot Boys - Guerrilla Warfare (1999)

The Hot Boys’ Guerrilla Warfare is a fiery example of late-90s New Orleans Hip Hop, capturing Cash Money Records in its golden era. With Juvenile, B.G., Turk, and a teenage Lil Wayne at the helm, the album overflows with street energy, charisma, and Mannie Fresh’s unmistakable bounce-driven production. It’s an album that thrives on chemistry, trading verses like sparring partners while anchored by the sonic brilliance of Mannie Fresh.

The production is a masterclass in regional flavor. Mannie Fresh’s beats are frenetic yet precise, blending New Orleans bounce with layers of pulsating bass, playful synths, and snapping hi-hats. Tracks like “We On Fire” are built on call-and-response hooks and bold, repeating phrases, giving each member a chance to shine while keeping the momentum relentless. The song’s infectious structure—with the repeated “What kinda nigga…” line—demands attention and serves as a statement of the group’s swagger.

Tracks such as “I Need a Hot Girl” and “Tuesday & Thursday” highlight the album’s versatility. The former, a radio-ready anthem featuring Big Tymers, rides a hypnotic, mid-tempo groove while blending playful and braggadocious lyrics. The latter offers a more paranoid, streetwise narrative, reflecting the constant surveillance and danger in their environment. Mannie Fresh’s knack for balancing gritty themes with infectious rhythms ensures the album never loses its bounce, no matter how heavy the subject matter gets.

Individually, the Hot Boys bring distinct styles that elevate the group dynamic. Juvenile’s confident drawl and storytelling, B.G.’s gritty realism, Turk’s straightforward delivery, and Lil Wayne’s youthful charisma create a compelling mix. While Wayne was still finding his footing as an MC, his energetic presence on tracks like “Respect My Mind” hints at the superstar he’d become.

Guerrilla Warfare isn’t without its flaws—some tracks like “Off Tha Porch” and “Sick Uncle” feel more like filler—but the group’s chemistry and Mannie Fresh’s cohesive production hold it together. This album isn’t just about individual brilliance; it’s about the collective power of the Hot Boys and Cash Money Records in their prime. A cornerstone of Southern Hip Hop, Guerrilla Warfare remains essential listening for its energy, style, and unapologetic celebration of New Orleans’ rap dominance.

Mac - World War III (1999)

Mac’s World War III (1999) is a standout album in the No Limit catalog, marked by its focused storytelling, deep introspection, and a departure from the label’s typical formula. While Beats by the Pound, No Limit’s in-house production team, contributed only sparingly, the album’s sound still channels the grimy, bass-heavy energy of Southern Hip Hop, blending melodic elements with the tension of street narratives. Mac’s lyricism is razor-sharp throughout, and his commanding delivery gives every track weight.

The opener, “War Party,” immediately establishes the album’s combative tone, with Mac’s gritty flow matched by aggressive verses from Magic and D.I.G. This sets the stage for a project that moves fluidly between heavy street anthems and introspective cuts. Tracks like “Assassin Nation” highlight Mac’s ability to craft vivid, cinematic imagery of violence and betrayal, while songs like “Like Before” explore more tender, reflective themes. The latter is a love song, surprisingly heartfelt for a gangsta rap album, with Mac’s voice showing a vulnerability that contrasts with the harder moments.

The production on World War III maintains a cohesive, Southern sound while leaning toward a stripped-back style that lets Mac’s verses take center stage. While some beats mirror No Limit’s signature aesthetic, there’s a subtle versatility in how they support Mac’s storytelling. Tracks like “Battle Cry” pulse with urgency, while “Best Friends” pairs a somber melody with deeply personal lyrics about loyalty and loss.

Clocking in at over 70 minutes, the album might be lengthy, but it rarely loses momentum. Skits are minimal, allowing the music to carry the narrative, and the sparse use of features—Master P, Mia X, and C-Murder make brief but effective appearances—keeps the focus squarely on Mac. His ability to balance street-level realism with moments of moral introspection elevates the album beyond a standard gangsta rap release.

World War III is a showcase of Mac’s lyrical and artistic range. It’s an album that draws strength from its cohesiveness, balancing hard-hitting tracks with poignant moments, cementing Mac’s reputation as one of No Limit’s most skilled and underappreciated artists.

Mystikal – Let’s Get Ready (2000)

Mystikal’s Let’s Get Ready, released in 2000, signified a significant shift in his career. Leaving behind the No Limit Records stable, Mystikal connected with a wider range of producers, resulting in a more diverse and commercially successful sound. This album, with its blend of high-energy delivery and varied production styles, propelled Mystikal to mainstream recognition.

The album’s most notable track, “Shake Ya Ass,” produced by The Neptunes, became a cultural phenomenon. The song’s infectious beat, with its distinctive synth melody and driving rhythm, created a party atmosphere that dominated airwaves and clubs. Mystikal’s energetic delivery, with his signature shouts and ad-libs, added to the song’s excitement. The track’s structure is simple yet effective, with a catchy chorus and memorable verses that encourage movement.

While “Shake Ya Ass” brought Mystikal widespread attention, Let’s Get Ready offers a range of sonic experiences. The Medicine Men, formerly known as Beats By the Pound, handle a significant portion of the production, providing a mix of hard-hitting beats and funk-influenced grooves. Tracks like “Ready to Rumble” have a confrontational energy, with Mystikal’s aggressive delivery matching the intensity of the production.

Other tracks, like “Danger (Been So Long),” also produced by The Neptunes, explore different moods. This song, featuring Nivea, has a smoother, more melodic feel, with a catchy hook and a slightly slower tempo. It offers a change of pace from the album’s more frenetic moments, demonstrating Mystikal’s ability to adapt to different styles.

The album also includes collaborations with other artists, such as Da Brat and Petey Pablo on “Come See About Me.” This track has a more collaborative feel, with each artist contributing their own distinct style to the mix. The production, handled by P.A., provides a solid foundation for the various deliveries.

Though the album has high points, some tracks feel less developed. While Mystikal’s energy is a consistent feature, some of the production choices in the latter half do not match the quality of the earlier songs. Even with contributions from established producers like Earthtone III (OutKast’s production team), some tracks lack the distinct character of the album’s stronger moments.

Despite these inconsistencies, Let’s Get Ready is an important album in Mystikal’s discography. It displays his ability to connect with a wider audience while retaining his distinctive style. The album’s success confirmed his position as a prominent figure in Southern Hip Hop.

Turk - Young & Thuggin' (2001)

Turk’s Young & Thuggin’, released in 2001, dropped during Cash Money Records’ period of significant commercial success. This album, like many from the label at the time, features production handled almost entirely by Mannie Fresh, creating a consistent sonic backdrop for Turk’s rhymes. The music is defined by its heavy bass, often with a prominent 808, layered with melodic keyboard lines and a bounce-influenced rhythm, creating a sound designed for both club play and car stereos.

The album’s overall mood is one of street life, loyalty to crew, and material aspirations. Turk’s delivery is direct and straightforward, often focusing on descriptions of his experiences in the streets. While his lyrical complexity might not be the primary focus, his delivery has a distinct melodic quality, a trait that differentiates him within the Cash Money roster.

Tracks like “Bout To Go Down” exemplify Mannie Fresh’s production style. The beat is energetic, with a driving rhythm and intricate keyboard melodies that create a sense of movement. Turk’s rhymes fit comfortably within this framework, focusing on themes of confrontation and asserting dominance.

“Yes We Do” presents a darker, more intense atmosphere. The production has a menacing quality, with ominous synth lines and a heavy bassline that creates a sense of foreboding. Turk’s delivery here is more aggressive, reflecting the track’s mood.

The album includes the single “It’s In Me,” which has a catchy hook and a bounce-influenced beat. Turk’s delivery on this track is rhythmic and engaging, creating a song that is both accessible and representative of the Cash Money sound.

Like other Cash Money releases, Young & Thuggin’ includes numerous guest appearances from labelmates, including Lil Wayne, the Big Tymers, and other Cash Money artists. These features add variety to the album, with each artist bringing their own distinct style and energy. While some might view this as a formulaic approach, it was a defining characteristic of the label’s output during this era.

While the album maintains a consistent sound, some tracks stand out. “Project” is a good example of Turk’s capabilities, with a solid performance and varied production. “Hallways & Cuts” creates a darker, more evocative atmosphere, with vivid descriptions of life in the projects.

Although not very lyrically intricate, Young & Thuggin’ provides a clear picture of Turk’s style and the Cash Money sound of the early 2000s. The album’s focus on production and its simplistic but consistent mood make it a noteworthy entry in New Orleans Hip Hop.

Soulja Slim — The Streets Made Me (2001)

Soulja Slim’s The Streets Made Me (2001) blends grit, introspection, and raw charisma into a project that’s equal parts celebration and cautionary tale. Released during No Limit Records’ waning years, the album represents Slim’s determination to stand tall in the midst of an empire on the decline.

The production is split between a handful of Southern beatmakers, including XL, Suga Bear, and Ke’noe, who inject some needed life into the No Limit formula of the early 2000s. Tracks like “Straight to the Dance Floor,” which flips Michael Jackson’s “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough,” balance playfulness with a club-ready bounce. Meanwhile, darker cuts like “My Jacket” bring a weightier energy, with Slim’s storytelling putting listeners front and center in the chaos and paranoia of street life. His ability to paint these vivid scenes—whether it’s surviving betrayal or flexing his resilience—cements his reputation as one of New Orleans’ sharpest lyricists.

Slim’s delivery is commanding throughout the album. His drawl, punctuated with blunt honesty, carries tracks like “Get Your Mind Right” and “What You Came Fo’.” Even when his themes veer into familiar territory—hustling, loyalty, and survival—there’s an edge to his voice that makes it feel authentic. Slim rarely wastes a bar, and his verses often outshine the contributions of the album’s minimal guest features. On “Ya Heard Me,” he glides over the beat effortlessly, contrasting the stiff delivery of his collaborators.

The album’s 20 tracks do feel overstuffed at times, a frequent issue with No Limit releases, but Slim’s presence anchors even the weaker moments. Interspersed with dirty club tracks and raunchy humor, the record reflects Slim’s personality: multifaceted and deeply rooted in the streets.

While The Streets Made Me doesn’t match the intensity of his earlier Give It 2 ’Em Raw, it’s a strong statement from an artist carving his own lane in a city overflowing with talent. Tragically, it would be one of Slim’s final projects before his untimely death in 2003, but his voice and stories remain a vital part of New Orleans Hip Hop history.

Big Tymers – Hood Rich (2002)

Big Tymers’ Hood Rich is built on Mannie Fresh’s infectious, endlessly creative production and Birdman’s flair for extravagant braggadocio. Packed with humor, decadence, and undeniably catchy beats, the album delivers a mix of anthemic tracks and playful cuts that embody the essence of Cash Money’s reign during this era.

The centerpiece of Hood Rich is the massive hit “Still Fly,” a track that combines absurdist humor with undeniable charm. Over a jubilant beat laced with horns and sparkling keys, Birdman and Mannie Fresh paint a portrait of “hood rich” living: designer clothes, flashy cars, and financial recklessness. The hook, sung with a mix of swagger and self-awareness, captures the absurdity of living large while being broke. It’s both hilarious and magnetic, the kind of song that sticks in your head for days.

The rest of the album largely follows suit, with Mannie Fresh providing a dynamic range of beats that keep the energy high. Tracks like “Oh Yeah” and “Hello” lean into vibrant, bouncy rhythms, pairing slick hooks with humorous boasts. Fresh’s production is meticulous without ever sounding overworked—horn stabs, layered percussion, and funky basslines dominate the record, creating a sound that feels lush and celebratory.

Guest appearances add variety, though the absence of the Hot Boys is notable. Instead, collaborators like Boo & Gotti and TQ step in, with mixed results. TQ’s crooning on “Sunny Day” and “Gimme Some” adds a smooth, R&B flavor, offering moments of contrast to the album’s otherwise high-energy tracks.

Lyrically, Hood Rich stays firmly in Cash Money’s wheelhouse: cars, women, and money. Birdman and Mannie Fresh are ar from the best or most complex lyricists, but their playful delivery and comedic timing keep things engaging. Songs like “#1 Stunna” and “Pimpin’” revel in their over-the-top excess, while others, like “Get High,” lean into laid-back vibes.

Ultimately, Hood Rich thrives on its ability to entertain. It’s not an introspective or groundbreaking record, but that’s beside the point. The album is a celebration of extravagance, with Mannie Fresh’s impeccable production serving as its driving force. Whether cruising through the streets or throwing a party, Hood Rich delivers the fun.

Juvenile – Juve The Great (2003)

Released at a turning point in Juvenile’s career, Juve the Great reflects an artist straddling two worlds—his established roots with Cash Money Records and his efforts to expand beyond its bounds. The album captures the essence of New Orleans Hip Hop, driven by Mannie Fresh’s iconic production and Juvenile’s distinctive, gravelly delivery, which carries a sense of authority and grit.

The album opens with “Intro (Juvenile/Juve The Great),” an assertive declaration that sets the stage with buoyant horns and a celebratory tone, underscoring Juvenile’s confidence in his UTP collective. This energy continues on “In My Life,” where Mannie Fresh crafts a bouncing, snare-heavy beat that feels like a throwback to Juvenile’s 400 Degreez era. Juvenile’s verses on the track balance introspection with swagger as he reflects on his journey and ambitions.

One of the album’s standouts, “Bounce Back,” features a Cameo sample woven seamlessly into Mannie Fresh’s production. The track’s upbeat tempo and playful rhythm are paired with Juvenile’s determination to reclaim his spot in the game, with Birdman delivering his signature braggadocio as a guest. This interplay of weighty lyrics and lighthearted beats runs throughout the album, offering a mix of hard-edged street anthems and moments of celebratory release.

“Slow Motion,” the album’s crown jewel, closes Juve the Great on a poignant note. Built on a hypnotic acoustic guitar loop by producer Dani Kartel, the track’s seductive, slow-paced rhythm contrasts its bittersweet legacy. Soulja Slim, who delivers the memorable hook, was tragically murdered before the song’s release, lending a somber aura to what became Cash Money’s first number-one hit. Juvenile’s verses on “Slow Motion” embrace themes of sensuality and indulgence, yet the track’s atmosphere is underpinned by Slim’s untimely death, making it a hauntingly fitting closer.

While the album occasionally shifts between Juvenile’s collaborations with UTP and his Cash Money roots, it manages to stay cohesive. Tracks like “Cock It” and “Enemy Turf” bring variety with distinct production styles, though the absence of more Mannie Fresh beats is noticeable. Still, Juve the Great encapsulates Juvenile’s ability to thrive in transition, offering a mix of celebratory anthems, reflective narratives, and undeniable Southern bounce.

Lil Wayne — Tha Carter (2004)

Lil Wayne’s Tha Carter, released in 2004, represents a distinct shift in his artistic direction. While his previous work with the Hot Boys and early solo albums leaned heavily on the established Cash Money sound, Tha Carter finds Wayne beginning to develop his own unique style. The album retains some of the label’s signature elements, particularly Mannie Fresh’s production, but it also reveals a growing lyrical complexity and a more assertive vocal presence from Wayne.

The album’s opening, “Walk In,” immediately establishes a different atmosphere. Over a dark, gritty beat by Mannie Fresh, Wayne delivers a dense, hookless verse, setting the scene with vivid imagery of his “Carter” building, a metaphor for his drug operations and burgeoning empire. The mood is serious and focused, a departure from the more lighthearted tone of some of his earlier work.

“Go DJ,” one of the album’s most recognizable tracks, offers a contrasting energy. The beat is upbeat and catchy, with a prominent synth melody and a driving rhythm. Wayne’s delivery is playful and energetic, showcasing his developing sense of humor and wordplay. This track, along with “Bring It Back,” provides the album with its more accessible, radio-friendly moments.

However, Tha Carter also explores deeper themes. “I Miss My Dawgs,” featuring Reel, is a reflective track that addresses the changes within Cash Money and the absence of former Hot Boys members. The production here is more melancholic, with a somber melody and a slower tempo, creating a sense of longing and nostalgia.

Tracks like “BM J.R.” display Wayne’s increasing lyrical dexterity. Over a hard-hitting beat, he delivers a barrage of complex rhymes and intricate wordplay, demonstrating his growing confidence as a lyricist. The song has a frantic energy, reflecting the intensity of Wayne’s delivery.

While Mannie Fresh handles the majority of the production, other producers like The Architects and Raj Smoove contribute to the album’s sonic variety. “Tha Heat,” produced by Raj Smoove, has a sinister feel, with a dark, ominous beat that creates a tense atmosphere.

The album’s structure, with its mix of energetic club tracks, introspective moments, and lyrical showcases, provides a well-rounded listening experience. While some tracks might not have aged as well as others, Tha Carter is a significant step in Lil Wayne’s artistic evolution, revealing the beginnings of the distinctive style that would later define his career.

Mannie Fresh – The Mind Of Mannie Fresh (2004)

Mannie Fresh’s The Mind of Mannie Fresh is an unapologetically maximalist project, packed with 30 tracks that straddle the line between genius and excess. Known as the sonic architect behind Cash Money Records’ iconic sound, Fresh uses this solo effort to dive headfirst into his creative world, blending his signature bounce with playful humor, regional pride, and unapologetic absurdity.

At its best, the album delivers undeniable party anthems and funky, brass-heavy beats that highlight Fresh’s unparalleled knack for crafting hooks. Tracks like “Real Big” exemplify his ability to transform the mundane into something celebratory. With its booming bassline and hypnotic repetition of everyday luxuries—cars, rims, and houses—the track exudes a carefree confidence and undeniable energy that defined early 2000s Southern Hip Hop. “Chubby Boy” is another standout, with its infectious rhythm and self-deprecating charm, showing Mannie’s gift for making tracks that are simultaneously goofy and commanding.

Structurally, the album is sprawling, with skits and interludes almost outnumbering full-length songs. While this approach gives insight into Mannie’s mischievous personality, it also bloats the album, making the 79-minute runtime feel overwhelming. The humor lands in places—particularly in the marching band-inspired intro, which blends soulful horns with percussion that feels like a halftime show on steroids—but elsewhere, the skits can veer into filler territory.

Vocally, Mannie keeps things simple, relying on charisma over lyrical complexity. Tracks like “We Fresh” and “How We Ride” balance his straightforward rhymes with the kind of bold, celebratory production that keeps heads nodding. However, his limitations as a rapper become more apparent on weaker tracks, like “Go With Me,” where a lackluster beat and flat verses fail to hold attention.

Ultimately, The Mind of Mannie Fresh is as chaotic as it is entertaining. It’s a sprawling portrait of a producer willing to experiment, for better or worse. While its length and inconsistency can detract, the highs—those undeniable beats and Mannie’s charm—make it a worthwhile ride through one of Hip Hop’s most inventive minds.

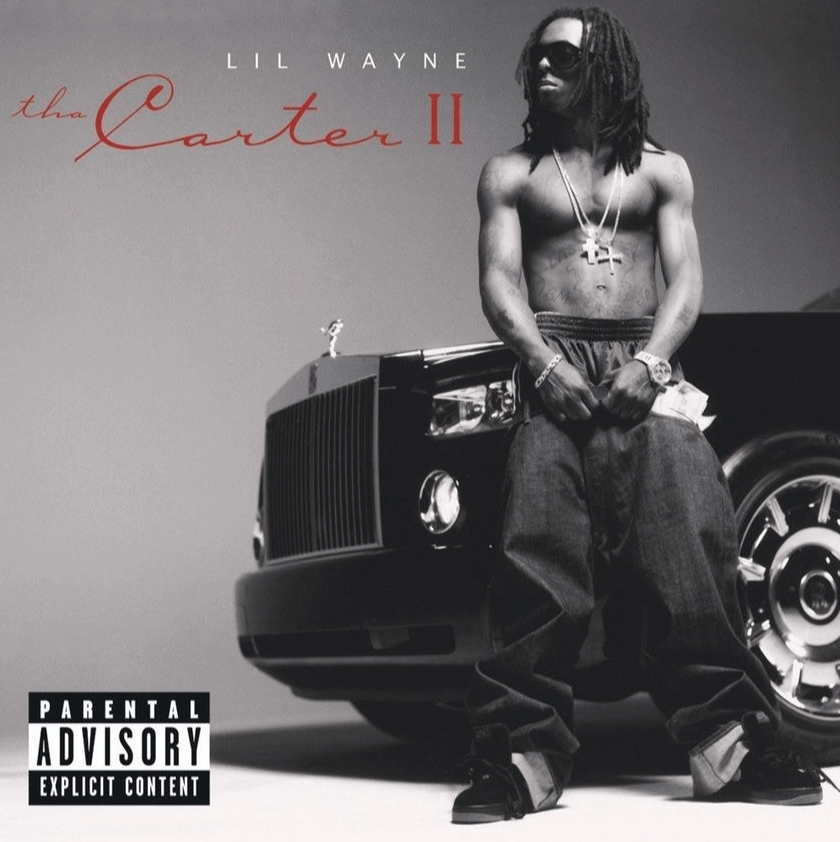

Lil Wayne - Tha Carter II (2005)

Lil Wayne’s Tha Carter II is an album that strikes with confidence, ambition, and a sharpened sense of artistry. Coming in at 22 tracks and over 77 minutes, this sprawling project sees Wayne pushing his lyrical dexterity and charisma to new levels, shedding the shadows of his early career to embrace a more complex and mature identity. Without Mannie Fresh’s production for the first time on a major release, Tha Carter II feels stripped down yet elevated, with its moody, Southern-rooted beats creating the perfect atmosphere for Wayne to shine.

The album opens with “Tha Mobb,” a five-minute statement piece that pulls listeners in with its brooding, bass-heavy production and relentless verses. Wayne’s flow here is methodical yet relentless, bending and stretching words with a swagger that shows his growth as an MC. The absence of a chorus feels intentional, giving the track a raw edge that sets the tone for the rest of the album. Similarly, “Fly In” acts as a hypnotic prologue, with Wayne riding the beat’s subtle piano and drum loops like a seasoned navigator, weaving together sly boasts and introspective bars with ease.

Lead single “Fireman” brings the heat with its thumping drums and infectious hook, cementing Wayne’s ability to craft a radio-friendly hit without sacrificing technical skill. “Hustler Musik,” on the other hand, offers a more reflective side, its soulful backdrop and melodic delivery giving space for Wayne to dissect his grind with a sense of urgency. Tracks like “Shooter,” featuring Robin Thicke, experiment with genre, blending jazzy undertones with a haunting vocal sample, while “Mo Fire” dips into reggae, showing Wayne’s willingness to step outside the usual Southern Hip Hop framework.

Lyrically, Tha Carter II swings between braggadocio and introspection. Wayne’s verses often touch on themes of success, loyalty, and survival, with occasional nods to social and political issues, like on “Feel Me,” where he acknowledges the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Still, much of the album leans on traditional Hip Hop tropes—money, power, and dominance—which, while engaging, sometimes leave you wishing for deeper explorations of Wayne’s potential for storytelling.

Production-wise, the album benefits from a variety of contributors, including Cool & Dre, The Heatmakerz, and T-Mix, who craft a dark, soulful aesthetic that complements Wayne’s raspy voice and elastic delivery. While not every track sticks, the cohesiveness of the sound ensures the album’s momentum rarely falters.

With Tha Carter II, Wayne positions himself as a force in Hip Hop, proving that technical skill and commercial appeal can coexist. It’s not flawless, but it’s an undeniable moment of growth that would soon pave the way for his dominance in the years to come.

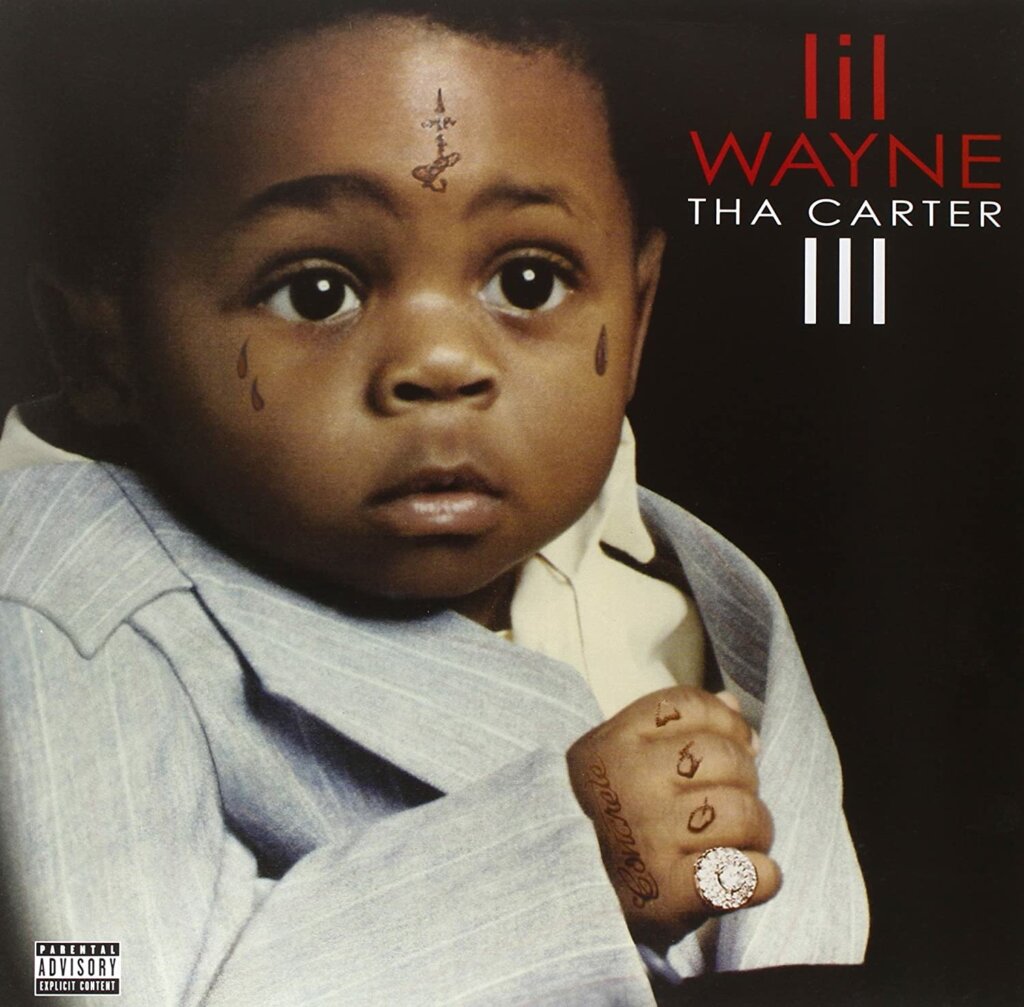

Lil Wayne - Tha Carter III (2008)

Lil Wayne’s Tha Carter III is an eclectic display of eccentric creativity that confirmed his place as one of Hip Hop’s most unconventional stars. With its mix of explosive bangers, introspective storytelling, and unapologetic weirdness, the album captures a moment when Wayne was at the peak of his powers, bending the genre to his will.

The production is bold and varied, swinging from the bass-heavy minimalism of “A Milli” to the jazzy intricacies of “Dr. Carter.” “A Milli,” built on a hypnotic loop and thunderous drums, strips Hip Hop to its essence, giving Wayne the space to weave bizarre, free-associative bars with his signature growl and off-kilter delivery. It’s pure bravado, with lines so wild they blur the line between nonsense and genius. On “Dr. Carter,” he shifts gears entirely, taking on the role of a physician reviving dying rappers while rapping over a chopped David Axelrod sample. Here, Wayne’s lyricism takes center stage, dissecting the elements of artistry with cleverness and humor.

Commercial hits like “Lollipop” and “Got Money” cater to the mainstream without sacrificing Wayne’s quirkiness. “Lollipop” blends auto-tune crooning with a futuristic beat, creating a club anthem that feels alien and unmistakably his. Meanwhile, “Tie My Hands,” featuring Robin Thicke, brings a somber gravity to the album, reflecting on post-Katrina New Orleans with sincerity and heart. Tracks like these show Wayne’s ability to balance playfulness with depth.

What ties the album together is Wayne’s voice—not just his literal rasp, but the way he uses it as an instrument. He stretches syllables, twists cadences, and dives headfirst into unpredictable flows. On “Let the Beat Build,” Kanye West’s gradually intensifying production sets the stage for Wayne to toy with the beat, building his verses with a controlled chaos that mirrors the track’s structure.

At 16 tracks, Tha Carter III isn’t without missteps. Songs like “La La” feel underdeveloped, and the album’s back half occasionally drags. But even when it stumbles, the sheer audacity of Wayne’s ideas keeps it compelling. Tha Carter III is a snapshot of an artist pushing himself in every direction, and even when it veers into the absurd, it never loses its spark.

Curren$y - Pilot Talk Trilogy (2010 - 2017)

Pilot Talk: Trilogy (2017) brings together Curren$y’s first three Pilot Talk albums in one sprawling collection of 41 tracks, clocking in at over two hours of smooth, jazz-inflected Hip Hop. From the start, it’s clear that this is a complete experience—a well-rounded look at Curren$y’s unique brand of laid-back luxury rap, where the beats are as important as the rhymes, and the vibe is all about chill sophistication.

The first track, “Example,” sets the tone with its dreamy, soulful instrumental, giving listeners a preview of the laid-back energy that runs through the entire trilogy. As Curren$y flows through “Audio Dope II” and “King Kong,” the signature style that made him a staple of the independent Hip Hop scene is immediately apparent: crisp, hard drums paired with smooth, looping jazz melodies, and a steady, almost meditative flow.

“Breakfast,” a standout track from the first Pilot Talk album, is classic Curren$y, effortlessly detailing his perfect morning ritual while the horns drift and the bass rumbles beneath him. The song perfectly embodies the album’s aesthetic—luxurious but not flashy, slow but not lethargic. The guest features on Pilot Talk: Trilogy are notable, with contributions from Mos Def and Jac Electronica on “The Day,” and Big K.R.I.T. & Smoke DZA on “Skybourne,” giving the project a well-rounded feel, but Curren$y remains the star throughout, never losing his cool, introspective vibe.

On Pilot Talk II, tracks like “Michael Knight” and “Famous” continue the themes of vintage cars, smooth living, and relaxed ambition, while the production from Ski Beatz remains jazzy and experimental, incorporating live instrumentation that feels both luxurious and natural. “Flight Briefing,” with Trademark & Young Roddy, is another highlight, combining Curren$y’s characteristic nonchalance with a slick, low-key beat.

By the time Pilot Talk III arrives in the trilogy, the production has deepened and expanded, with tracks like “Froze” (featuring Riff Raff) and “Pot Jar” (featuring Jadakiss) showing a sharper, more refined side of Curren$y. The guest appearances, which also include Fiend and Raekwon, bring fresh energy to the album without disrupting its serene atmosphere.

Ultimately, Pilot Talk: Trilogy is a cohesive work that builds on itself with each album. Curren$y’s consistent blend of mellow vibes, luxurious raps, and introspective moments creates a singular atmosphere that holds up over the course of 41 tracks. Whether he’s detailing his day-to-day life or contemplating his place in the world, Curren$y keeps it cool, keeping listeners engaged with his signature style of relaxed, but sharply detailed storytelling. This trilogy is a mood—and once you’re in it, you won’t want to leave.